The Control of Nature

What We Owe Our Trees

Forests fed us, housed us, and made our way of life possible. But they can’t save us if we can’t save them.

By Jill Lepore

From the issue of May 29, 2023, issue of The New Yorker Magazine

The Wisconsin legislature in 1867 commissioned an investigation that resulted in the publication of:

“Report on the Disastrous Effects of the Destruction of Forest Trees, Now Going On So Rapidly in the State of Wisconsin.”

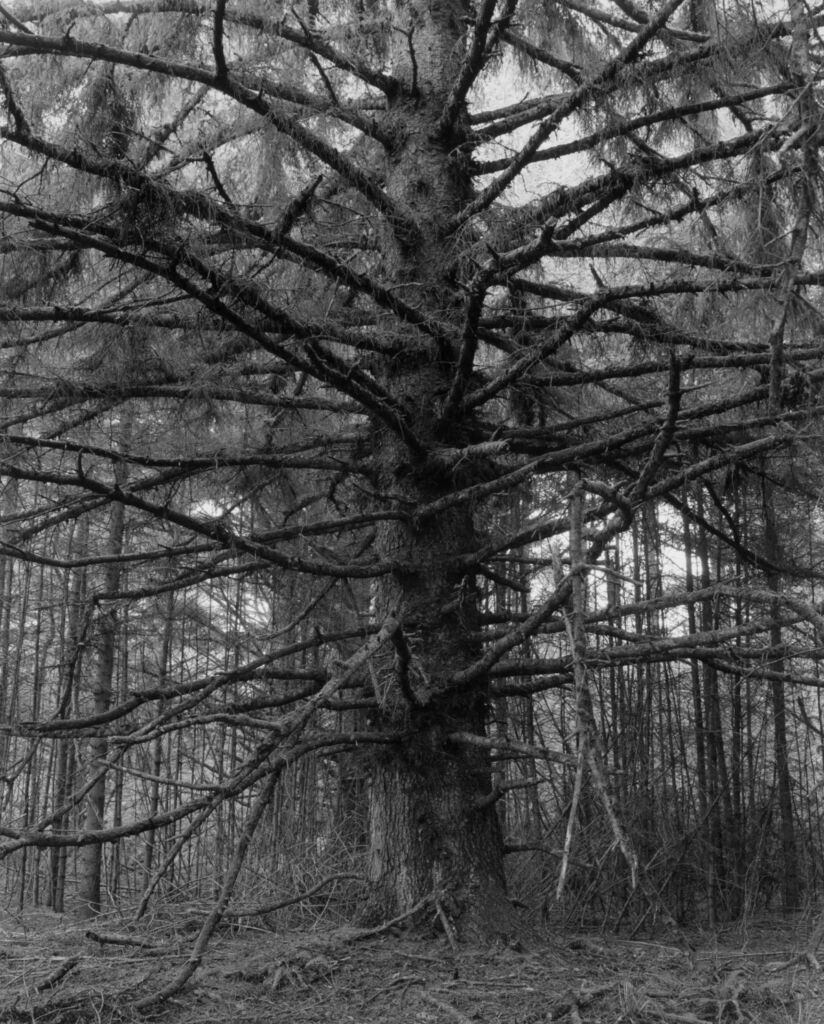

The woods I know best, love best, are made of Northern hardwoods, sugar maple and white ash, timber-tall; black and yellow birch, tiger-skinned; seedlings and saplings of blighted beech and striped maple creeping up, knock-kneed, from a forest floor of princess pine and Christmas fern, shag-rugged. White-tailed deer dart through softwood stands of pine and hemlock, bucks and does, the last leaping fawn, leaving tracks that look like tiny human lungs, trails that people can only ever see in the snow, even though, long after snowmelt, dogs can smell them, tracking, snuffling, shuddering with the thrill of the hunt and noshing on deer scat for dog treats. I make lists of finds, two-winged, four-footed, and rolling: black-throated green warblers and blue-headed vireos, porcupines and salamanders, tin cans and old tires, deer mice and fisher cats, wild turkeys and ruffed grouse, black bears and, come spring, their tumbling, potbellied, big-eared cubs.

Even if you haven’t been to the woods lately, you probably know that the forest is disappearing. In the past ten thousand years, the Earth has lost about a third of its forest, which wouldn’t be so worrying if it weren’t for the fact that almost all that loss has happened in the past three hundred years or so. As much forest has been lost in the past hundred years as in the nine thousand before. With the forest go the worlds within those woods, each habitat and dwelling place, a universe within each rotting log, a galaxy within a pine cone. And, unlike earlier losses of forests, owing to ice and fire, volcanoes, comets, and earthquakes—actuarially acts of God—nearly all the destruction in the past three centuries has been done deliberately, by people, actuarially at fault: cutting down trees to harvest wood, plant crops, and graze animals.

“Like rude house guests who arrive at the last minute, cause havoc and set about destroying the house to which they have been invited, human impact on the natural environment has been substantial and is accelerating to the point that many scientists question the long-term viability of human life.”

— Peter Frankopan, The Earth Transformed

The Earth is about four and a half billion years old. By about two and a half billion years ago, enough oxygen had built up in the atmosphere to support multicellular life, and by about five hundred and seventy million years ago the first complex macroscopic organisms had begun to appear, as Peter Frankopan reports in “The Earth Transformed” (Knopf), an essential epic that runs from the dawn of time to, oh, six o’clock yesterday. In his not at all cheerful conclusion, looking to a possibly not too distant future in which humans fail to address climate change and become extinct, Frankopan writes, “Our loss will be the gain of other animals and plants.” An upside!

The first trees evolved about four hundred million years ago, and pretty quickly, geologically speaking, they covered most of the Earth’s dry land. A hundred and fifty million years later, during a mass-extinction event known as the Great Dying, the forests perished, along with nearly everything else on land and sea. Then, two million years after that, the supercontinent broke up, a seismic process whose consequences included depositing oil, coal, and natural gas in the places on the planet where they can still be found, to our enrichment and ruination. The trees returned. The ginkgo is the oldest surviving tree species, its fan-shaped leaves unfurling lime green in spring and falling, mustard yellow, in autumn.

The first primates showed up about fifty-five million years ago, in the rain forest. They lived in the trees. Our ancestors began dividing from apes—began, slowly, coming down from the trees—about seven million years ago; the genus Homo branched off four million years later; and Homo sapiens began wandering around the understory somewhere between eight hundred thousand and two hundred thousand years ago, although exactly when is apparently a matter of fierce debate, which seems right, since humans are such a contentious, Neanderthal-killing lot. Here’s how Frankopan, a professor of global history at Oxford, puts it: “Like rude house guests who arrive at the last minute, cause havoc and set about destroying the house to which they have been invited, human impact on the natural environment has been substantial and is accelerating to the point that many scientists question the long-term viability of human life.” Climate change contributed to the extinction of Neanderthals about thirty-five thousand years ago, but humans, instead of dying out, migrated to different climates, or found other ways to survive, which generally involved controlling fire and burning fallen sticks and branches for heat and to cook otherwise hard-to-digest food, or making axes to cut down trees, whose wood could be used to build shelters and, later, fences for animals. They cut and felled. Knopf printed about twenty thousand copies of Frankopan’s seven-hundred-page book on paper made from trees. I read it sitting in a house built of pine in a chair made of maple at a desk made of oak holding a pencil made of cedar. They cut and felled. The wood in my woodstove is yellow birch, burning, bark curling.

“If you think about it, a tree is a tricky place in which to live,” the biologist Roland Ennos writes in “The Age of Wood” (Scribner). Ennos argues that dividing human history into the Stone Age (beginning two and a half million years ago), the Bronze Age (3000–1000 B.C.E.), and the Iron Age (1200–300 B.C.E.)—a scheme invented in the nineteenth century by a Danish antiquarian—misses the earliest and most important era, the Wood Age.

People are arboreal, at least vestigially, Ennos points out, with binocular vision, upright posture, hind limbs for movement, forelimbs for gripping, and fingers with soft pads and nails, all features that evolved to help primates live in trees. The first primates were as small as mice, and could scramble wherever they liked, but, as they got bigger, it became harder to stay up in the trees, where it was safest, especially at night. A “clambering hypothesis,” among primatologists, has it that the thinking of great apes got more sophisticated—they developed a “self-reflective psychology”—so that they could better understand the mechanics of climbing and swinging through trees. Also, the first tools used by great apes were made of trees and in trees: nests for sleeping in higher branches. (The bigger your brain, the more rem sleep you need.) The earliest hominins who learned to walk upright did so while still living, mainly, in trees, and they came down at night only after figuring out how to make fires—with wood. That had all kinds of knock-on effects, including being able to cook food, which makes it easier for us to get energy out of it, and made it possible for our brains to grow bigger. Hominins came down from the trees, built huts, made fires, and no longer needed their fur, so they lost it, which meant that when the weather, or the climate, got colder they needed warmer huts and more fires, but with those they could go anywhere, as long as there were trees. As for making tools, they mainly used not stone but wood, and when they did use stone it was often to make better tools out of wood. You could use a stone, for instance, to sharpen a wooden spear, a tool you could wield to kill beasts of land and sea.

In all this time, people did not run out of wood, since there weren’t that many people and there were a great many trees, and because trees grow back. Even after humans invented the stone axe and began to chop down trees, this was still true. Chopping and burning, they cleared openings in forests to attract game, and they adzed trunks and limbs into poles and posts, planks and beams. They built houses and rafts and boats, and some people, in places where they had cleared the forests, began to farm. During the ages of stone, bronze, and iron, down through the early modern era, Ennos writes, “almost all the possessions of everyday folk were wooden, while those that were not actually made of wood needed large quantities of wood to produce.” Only the turn to coal for fuel in the eighteenth century and to wrought iron for building in the nineteenth, he argues, brought about the end of the age of wood. Except that it didn’t exactly end, since imperialism, industrialism, and capitalism meant that people were more likely to go to war and conquer land in order to cut down other people’s trees.

You could tell this story about a lot of places, but consider England and its North American colonies. By the eighteenth century, much of England and in fact much of Western Europe had been deforested, but England needed timber to build ships in order to trade goods, wage war, and found colonies. It especially wanted very tall and straight pines, for ships’ masts. During the long wars between Britain and France, often fought at sea, France had for a time a ship’s-mast advantage, having cut a path known as the Mast Road through the Pyrenees to a stand of tall fir trees. Britain harvested its masts from its colonies, and especially from the tall white pines of New England, having issued an edict, in 1691, that any pine whose trunk, when measured a foot from the ground, was more than twenty-four inches in diameter belonged to the King (later revised, fairly desperately, to twelve inches in diameter). Among the many causes of the American Revolution was the Pine Tree Riot of 1772, when New Hampshire mill owners refused to pay fines for sawing pine trees into boards.

One of the earliest alarms about deforestation written in English is “Sylva, or a Discourse on Forest-Trees, and the Propagation of Timber of His Majesties Dominions,” by Sir John Evelyn, published in London in 1664. Evelyn called for tree planting as an act of patriotism, and if he was the first to do so he was not the last, as the University of Oregon geographer Shaul E. Cohen reported in his book “Planting Nature: Trees and the Manipulation of Environmental Stewardship in America” (2004). Writing about forests, John Perlin urges humans to “stop our war against them” in a new edition of his 1989 book, “A Forest Journey: The Role of Trees in the Fate of Civilization” (Patagonia), more than five hundred pages but “printed on 100 percent postconsumer paper.” Yet any plans for a truce in this war, including calls for planting trees, have often been pretty suspect, perhaps especially so in the United States.

American states legislated the protection of the forests from the start, if to little effect. After the Revolution, for instance, Massachusetts forbade the cutting down of those twenty-four-inch white pines on any public lands. But in the Western territories “public lands,” which were generally the unceded ancestral homelands of tribal nations, quickly became private lands. After the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Congress paid Revolutionary War veterans in plots of land in the Northwest Territory, north of the Ohio River. (“The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress,” Congress affirmed in the Ordinance, in a pledge not honored.) In Conrad Richter’s 1940 historical novel, “The Trees,” a family from Pennsylvania treks to the Ohio Valley around 1787. Their little girl, looking down from a hilltop, is overwhelmed by her first view of the forest, thinking that “what lay beneath was the late sun glittering on green-black water,” mistaking for an ocean what was, instead, “a sea of solid treetops broken only by some gash where deep beneath the foliage an unknown stream made its way.” The whole of Richter’s trilogy, the story of American pioneers, is the story of clearing the woods: “Oh, it was hard beating back the woods. You had to fight the wild trees and their sprouts tooth and nail.” By the trilogy’s end, that little girl, now an old woman, is haunted by regret. “She reckoned she knew now how one of those old butts in the deep woods felt when all its fellows were cut down and it was left standing lone and gaunt against the sky, with only whips and brush and those not worth the axe pushing up around it. The second growth trees you saw today were mighty poor and spindly specimens beside the giants she had known when first she came to this country.”

A sense that the great clearing meant, as well, a great loss pervaded nineteenth-century American culture. Much of it was romance, a product of the wispy, dreamy, self-justifying association many Americans made between the vanishing forest and the imagined vanishing of the Indians, even while the federal and state governments pursued a policy of conquest and war against Native nations. Tree-planting campaigns became the called-for, remorseful remedy. “If our ancestors found it wise and necessary to cut down fast forests, it is all the more needful that their descendants should plant trees,” the landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing wrote in 1847. “Let every man, whose soul is not a desert, plant trees.” That same year, George Perkins Marsh gave a lecture in Rutland, Vermont, that helped launch the conservation movement. Marsh argued that the destruction of the forests had consequences for the climate: “Though man cannot at his pleasure command the rain and the sunshine, the wind and frost and snow, yet it is certain that climate itself has in many instances been gradually changed and ameliorated or deteriorated by human action.” He went on:

The draining of swamps and the clearing of forests perceptibly effect the evaporation from the earth, and of course the mean quantity of moisture suspended in the air. The same causes modify the electrical condition of the atmosphere and the power of the surface to reflect, absorb and radiate the rays of the sun, and consequently influence the distribution of light and heat, and the force and direction of the winds. Within narrow limits too, domestic fires and artificial structures create and diffuse increased warmth, to an extent that may effect vegetation.

Marsh insisted, “Trees are no longer what they were in our fathers’ time, an incumbrance.” They are, instead, a reservoir, the source of life, the regulators of the climate.

Marsh, a linguist and a diplomat, went on to write a groundbreaking book, “The Earth as Modified by Human Action,” first published in 1864 under the title “Man and Nature,” a nineteenth-century version of Frankopan’s “The Earth Transformed.” The Wisconsin legislature in 1867 commissioned an investigation that resulted in the publication of its “Report on the Disastrous Effects of the Destruction of Forest Trees, Now Going On So Rapidly in the State of Wisconsin.” The state then inaugurated a program of tax exemption for landowners who planted trees. In 1873, the Nebraska senator Phineas W. Hitchcock introduced the Timber Culture Act, declaring, “The object of this bill is to encourage the growth of timber, not merely for the benefit of the soil, not merely for the value of timber itself, but for its influence upon the climate.” The act, a failure, was repealed in 1891. Instead, the lasting consequence of Marsh’s “The Earth as Modified by Human Action” was Arbor Day, created by a Nebraskan named J. Sterling Morton and first celebrated on April 10, 1872.

Morton, the editor of the Nebraska City News, called for a day “set apart and consecrated for tree planting.” On that first Arbor Day, Nebraskans planted more than a million trees. The holiday soon spread, especially after Grover Cleveland appointed Morton as his Secretary of Agriculture, in 1892. The advocacy organization American Forests was founded in 1875, and, as Cohen writes, it also advanced the idea that planting a tree was an act of citizenship. This was a tradition that faltered at various times in the twentieth century but was renewed beginning in 1970 with the first Earth Day (also held in April) and with the establishment of the National Arbor Day Foundation two years later. Its many programs include Trees for America; pay a membership fee, and you get ten saplings in the mail. American Forests runs Global ReLeaf.

But Cohen and other critics have argued that there is little evidence that these programs do much more than greenwash bad actors. American Forests has been sponsored by both fossil fuel and timber companies. In 1996, the climate-change-denying G.O.P. encouraged Republican congressional candidates to have themselves photographed planting a tree. “10 Reasons to Plant Trees with American Forests,” printed in 2001, suggests that “planting 30 trees each year offsets the average American’s ‘carbon debt’—the amount of carbon dioxide you produce each year from your car and home.” The E.P.A., on a Web site that linked to American Forests, urged Americans to plant trees as penance: “Plant some trees and stop feeling guilty.” What with one thing and another, have you used ten thousand kilowatt-hours of electricity? The site offered indulgences: plant ten trees, one for every thousand kilowatt-hours. At the height of the corporate tree-atonement era, a New Yorker cartoon showed a queue of businessmen waiting to see a guru, with one saying to another, “It’s great! You just tell him how much pollution your company is responsible for and he tells you how many trees you have to plant to atone for it.”

The notion that clear-cutting can be counteracted by the planting of trees is a political product of the timber industry. As Cohen shows, the phrase “tree farm” was coined by a publicist at a timber company, as was the motto “Timber Is a Crop.” And the notion hasn’t died. In 2020, the World Economic Forum announced its sponsorship of an initiative called 1t, a corporate-funded plan to “conserve, restore, and grow” one trillion trees by the year 2030. At Davos in 2020, Donald Trump pledged American support. (At the time, the President mentioned that he was reading a book about the environmental movement; written by a former adviser of his, it was called “Donald J. Trump: An Environmental Hero.”)

It’s good to plant trees. No one’s arguing any different. “There’s no anti-tree lobby,” a Nature Conservancy ecologist told Science News recently. Trees are the new polar bears, the trending face of the environmental movement. But it’s not clear that planting a trillion trees is a solution. In terms of biodiversity, killing forests and planting tree farms isn’t much help; a forest is an ecosystem, and a tree farm is a monoculture. Forests absorb about sixteen billion metric tons of carbon dioxide every year, but they also emit about eight billion tons. The main study behind the 1t movement proposes that planting trees on land around the world roughly equivalent in area to the United States will trap more than two hundred billion tons of carbon. Yet a forum published in Science in 2019 expressed grave skepticism about both the science and the math behind this plan. The history is fishy, too. National tree-planting schemes have, historically, come up short. Studies across countries have found that as many as nine in ten saplings planted under these auspices die. They’re the wrong kind of tree. No one waters them. They’re planted at the wrong time of year. They have not improved forest cover. The 1t folks make a point of saying that they’re not planting trees; they’re growing them. But whether they really are remains to be seen.

In the meantime, you are asked to think differently about trees. They’re out there. They’re smart. They will outlast us. Brian Selznick’s graphic children’s novel “Big Tree” (Scholastic) tells the story of trees across tens of millions of years, through the trials of two sycamores: “Once upon a time, there were two little seeds in a very old forest. Their mama said she would give them roots and wings—roots so they’d always have a home, and wings so they would be brave enough to find it.” Selznick’s understanding of forestry, and maternal trees, borrows from the work of the Canadian ecologist Suzanne Simard. As a young scientist, Simard was the lead author of a study published in Nature, “Net Transfer of Carbon Between Ectomycorrhizal Tree Species in the Field,” in which she reported the findings of a years-long series of experiments that she conducted with seedlings. “Plants within communities can be interconnected and exchange resources through a common hyphal network, and form guilds based on their shared mycorrhizal associates,” she concluded. That is to say, plants can communicate with one another chemically, and across species, issuing warnings, for instance. Put in human terms, trees can care for one another. Simard came to call certain of these signallers “mother trees,” which both got her into hot water and made her beloved. Although subsequent research verified most of her major findings, she was for a long time chastised by scientists, an experience that was the inspiration for the trials of Patricia Westerford in Richard Powers’s intricate Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “The Overstory,” from 2018. In the novel, Powers describes the moment of Westerford’s crucial finding, in a forest of sugar maples:

The trees under attack pump out insecticides to save their lives. That much is uncontroversial. But something else in the data makes her flesh pucker: trees a little way off, untouched by the invading swarms, ramp up their own defenses when their neighbor is attacked. Something alerts them. They get wind of the disaster, and they prepare. She controls for everything she can, and the results are always the same. Only one conclusion makes any sense: The wounded trees send out alarms that other trees smell. Her maples are signaling.

Amy Adams is slated to play Simard in an upcoming film adaptation of Simard’s memoir, “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest” (Knopf).

Simard is herself something of a maternal spirit in Katie Holten’s collection of essays, poems, and other snippets, “The Language of Trees” (Tin House), in which Holten, an Irish artist and activist, introduces a tree alphabet. Each letter is represented by the striking silhouette of a tree: Apple, Beech, Cedar, Dogwood, Elm, and so on. The book reproduces a piece of Simard’s writing: “When mother trees—the majestic hubs at the center of forest communication, protection, and sentience—die, they pass their wisdom to their kin, generation after generation, sharing the knowledge of what helps and what harms, who is friend or foe, and how to adapt and survive in an ever-changing landscape. It’s what all parents do.” That “mother,” in Holten’s abecedary, reads this way: Mulberry, Oak, Tree of heaven, Horse chestnut, Elm, Redwood.

Simard’s research has also been popularized by a German forester named Peter Wohlleben in his best-selling 2015 book (first translated into English in 2016), “The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate.” Wohlleben’s earlier books were downers, like “The Forest: An Obituary.” “The Hidden Life of Trees” is not a downer. Forget imperialism, industrialism, and capitalism. Think feelings. A forest of trees, Wohlleben argues, is like a herd of elephants. “Like the herd, they, too, look after their own, and they help their sick and weak back up onto their feet.” Like elephants—like humans—trees have friends, and lovers, and parents and children. They have language, and they also have, he argues, a kind of sentience.

As science, the mothering, feeling tree is controversial. As literature for a political movement, it’s not bad, and, after all, nothing else has worked—not Arbor Day, not the “Report on the Disastrous Effects of the Destruction of Forest Trees, Now Going On So Rapidly,” not Global ReLeaf, not 1t. At this rate, unless humans think of something better fast, the forests, and then we who walk the Earth, two-legged, will be Dogwood, Elm, Apple, Dogwood. ♦