Can modular housing construction techniques help create quick and affording homes here in Arcata?

In the December 12, 2022, OLLI Affordable Housing presentation (link here), Danco President Chris Dart was asked about modular construction. In many instances, modular construction has resulted in a 20% reduction in the cost of actual construction. But — and this is a big “but” — there are many other costs involved in developing a property, other than the actual construction costs. And a definite limiting factor for us here on the North Coast is the cost of transportation for the modules.

The word “modular” is used in different ways, so let’s clarify. In the order of complexity:

- There is modular housing that consists of factory-made units for single-story detached housing — typically with units eight feet wide and homes made of 1, 2, or 3 widths. The units have a roof in place and are generally “stick-built,” framed with wood. This method of construction results in lower-cost single-family homes.

- Modular components for one-of-a-kind or small quantities of one- or two-story single-family homes. In cases of limited road access to the site, the modules can be airlifted via helicopter. Good for quick turn-around from site prep to move-in. Can be cost-effective in some circumstances, but lacking economies of scale of large factory production.

- Identical modular stacking units. Often the modular units are identical, but not necessarily. See the Santa Maria project, below, and others in this article. Often (but not necessarily) designed as long, narrow modules consisting of two ~350 sq.ft. studio apartments at each end and a hallway in the middle. The resulting apartments have windows only at one narrow end — not ideal from a quality of life perspective.

- Two or more types of modular components that “snap together” (not literally) to create a variety of apartment sizes and types. See the Berkeley Garden Village, below. This design has maximum flexibility and can be useful in smaller buildings, where each apartment has windows on corners and more than one wall. To me, this form of modular design and construction is ideal.

- A variety of combinations. The ground floor may be constructed on site of concrete/steel, and then modules stacked on top.

Some modules have the exterior cladding in place from the factory, and other designs have the exterior cladding put up on-site, after the modules are stacked. Some modules include all furniture and appliances for instant move-in — ideal for dorms or assisted supportive/transitional housing.

Modular housing could be an answer to the State housing crisis

The “Tahanan” permanent supportive housing complex in San Francisco had costs of $385,000 per unit and from announcement to occupancy was done in 3 years. More typical in San Francisco is a cost of $600,000 per small studio unit, and a time-frame of 5 to 7 or even 10 years.

According to the module factory promotions, modules can be assembled into apartment buildings 40% more quickly and 20% cheaper than traditional construction.

The articles below include modular units from factories in Vallejo, Sacramento, Klamath Falls OR, Idaho, Canada, and China.

Santa Maria, California

Five-Story Senior Housing Project Rises Quickly in South Santa Maria

160-unit Santa Maria Studios employs modular structures, hastening construction for the affordable apartment building

by Janene Scully published in Noozhawk – The Freshest News in Santa Barbara County

October 25, 2022

https://www.noozhawk.com/five_story_senior_housing_project_rises_in_south_santa_maria/

See also: https://prefablogic.com/project/santa-maria-studios/

A five-story-high senior apartment complex has sprouted seemingly overnight in southeast Santa Maria.

Construction continued Monday on the Santa Maria Studios, the first phase of a 160-unit project on the 2600 block of Santa Maria Way, near the intersection with Miller Street.

The apartment building is taking shape after the modular units were constructed in an Idaho factory and assembled on site as if they were building blocks.

Like any traditional project, the building eventually will be covered in stucco and have architectural features.

“By the end of the project, you wouldn’t even be able to tell the method of construction,” Santa Maria Community Development Director Chuen Ng said.

As the building has taken shape, the project has attracted criticism and misinformation among social media users.

The applicant filed the permit request under Senate Bill 35, which allows a developer proposing affordable housing to bypass the normal reviews, including by the local Planning Commission and City Council.

Last year, the mayor cited the development as an example of project where the city’s leaders have lost local control due to state rules.

That doesn’t mean they can avoid typical building codes, including those regarding earthquake safety or Americans with Disabilities Act requirements.

“We have to make sure that all new construction, new buildings meet all of the state’s building codes,” Ng said.

He added that the construction for Santa Maria Studios “is a little bit different” because it had used modular structures.

Late Monday afternoon, a huge crane lifted one of the rectangular structures into place to continue creating the fifth level.

“The interiors are actually almost done — there are kitchen cabinets inside, even appliances inside,” Ng added. “By the time they stack there, it just allows for faster construction.”

The project involves The Pacific Companies and Encino-based AMG Associates (unrelated to the AMG & Associates that built two new schools and is completing the Allan Hancock College Fine Arts Complex).

“It did kind of spring up overnight, but there’s still some work to do on this project,” Ng said.

The applicant submitted plans to the build the first 160 units, with a second phase calling for 218 units of affordable senior housing units, according to the Community Development Department.

“The applicant has not applied for building permits yet to build the second phase,” the city’s Planning Division Manager Dana Eady said.

The 160 studio units will all be located within one building. The project includes onsite parking, bike racks, landscaped outdoor seating areas, community rooms, and a dog park (for resident’s pets to use), Eady said.

Idaho-based PreFab Logic said rental estimates including utilities have been adjusted to between 30 and 60 percent of the area’s median income. This would mean more than half of the proposed rent rates are “at or under $1,000 per month.”

“While rents on these units will be low, the quality and amenities of these small studio apartments are very high, with quality fixtures and appliances, and ADA-compliant features, making quality housing more attainable for Santa Maria’s aging population,” the PreFab Logic website says.

The modular manufacturer said this was one of the first two senior housing projects built with a new kind of factory automation.

“Prefab Logic partnered with the factory to help produce the unique data set required to simplify the construction process for both robots and people working in the modular factory.”

Santa Maria Studios is one of multiple apartment projects under construction, with several others in the pipeline.

Also under construction are Centennial Gardens on West Battles Road near Depot Street, with 160 affordable units, and Centennial Square Apartments on the southeast corner of Miller Street and Plaza Drive.

Berkeley, California

Berkeley sprouts creative housing, topped by a working farm

by John King published in the San Francisco Chronicle

December 24, 2016

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Berkeley-sprouts-creative-housing-topped-by-a-10816953.php

See also:

https://www.aia.org/showcases/155456-garden-village

https://www.gardenvillageapt.com/

The unexpected twist in the new housing complex on Berkeley’s south side isn’t just the rooftop farm. It’s that the fields of edible greens rest above 18 freestanding structures, vertical pods, that hold 77 apartments in all.

Put those two elements in the middle of a fairly dense city, and they combine to make a point that’s easy to forget: Our society’s need for pedestrian-friendly housing doesn’t need to be satisfied in cookie-cutter ways.

This welcome fact runs counter to what we see in growing cities across the Bay Area, the state, even the nation as a whole — anywhere new housing is packaged in squat, costumed boxes along busy streets. The planning theory is great. The execution too often is generic at best.

Not so at the corner of Dwight Way and Fulton Street on the edge of downtown Berkeley, where the boxy collage of Garden Village is like nothing that you’ve seen.

The design is by Stanley Saitowitz, one of the region’s few architects whose work is always interesting — even his less-successful buildings don’t feel formulaic, because there’s an underlying concept that’s tied to aesthetics and the setting. In this case, the blocks south of UC Berkeley, where students inhabit everything from chopped-up single-family homes to small apartment buildings and high-rise dorms.

“Berkeley is a place of detached buildings,” said Saitowitz, who lives and works in San Francisco but taught at Cal’s College of Environmental Design for more than 30 years. “I wanted to explore how to add density within that tradition.”

Construction methods also shaped the design. Developer Nautilus Group, which also served as architect of record, wanted to use prefabricated components throughout the complex. That way, portions of the apartments could be manufactured elsewhere, then assembled on-site.

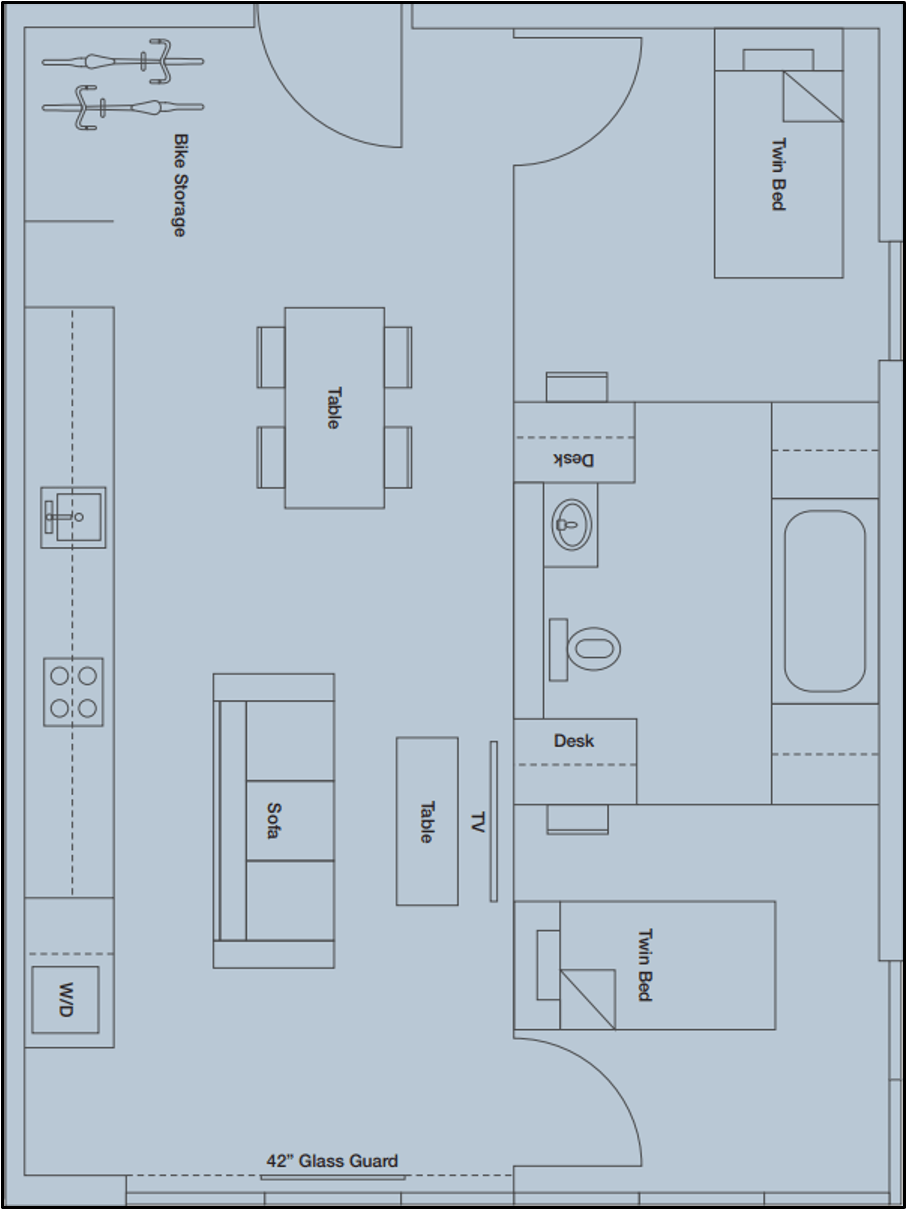

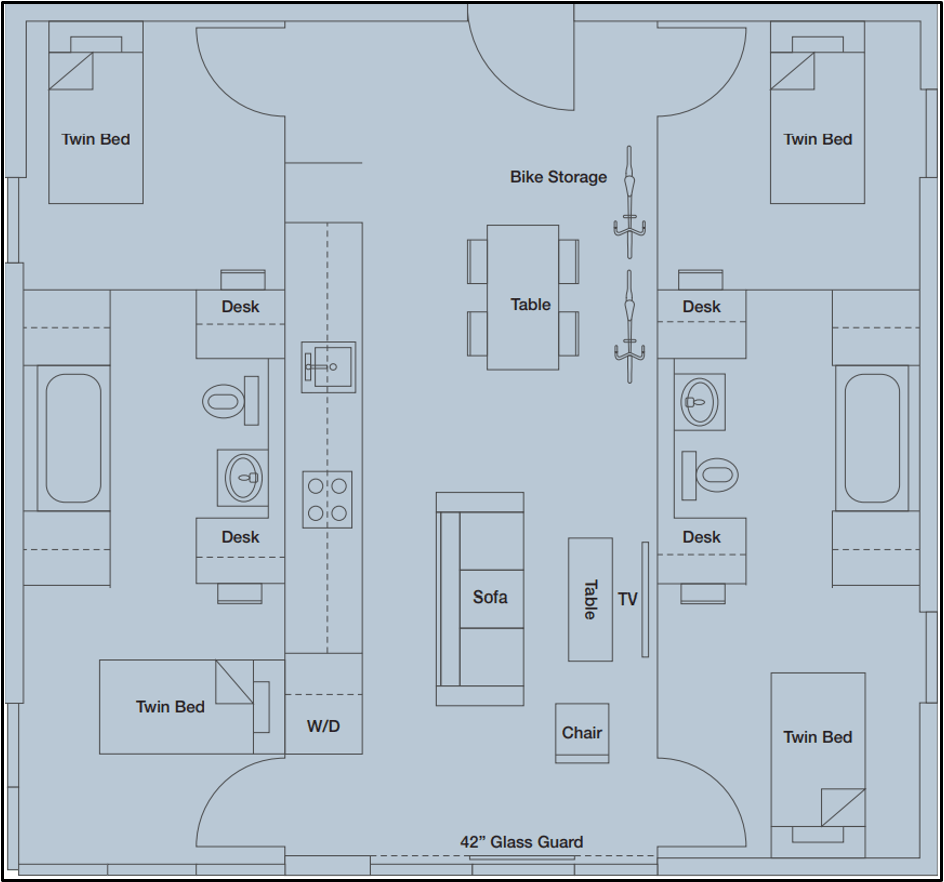

Saitowitz and his firm, Natoma Architects, responded with a system of two large modules — one containing two small individual bedrooms and a shared bathroom, the other holding the living, dining and kitchen areas. Snap two together, and you’ve got a two-bedroom apartment. Put bedroom modules on either side of the communal section, and it’s a four-bedroom suite.

That ingenuity helped Saitowitz get the job. The next step, how to deploy the modules, is what makes you stop and look twice.

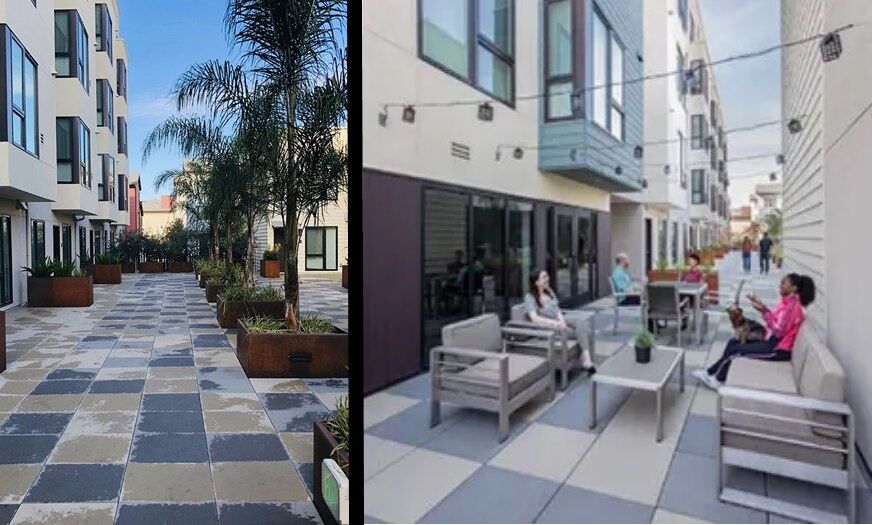

The “village” consists of 18 buildings of three to five stories, with each floor holding a separate apartment. The pod-like stacks are connected by steel bridges with open grillage below your feet. Where the bridges serve as walkways — outdoor corridors — the square buildings are 5 feet apart. Where there’s a ground-level landscape and fresh air up above, the width is as much as 15 feet, with protruding window frames to add a bit of privacy.

The specific numbers are less important than the overall impression — a grid brought to life in 3-D.

From the street the look can be forbidding, though Saitowitz clads every other pod in a dark red cement board. He calls it “my homage to Berkeley brown-shingle homes,” which also adds a contrast to the white pods in between. But the open-air corridors and multistory sight lines make the interior of the grid surprisingly cozy, with a collegial feel that’s much more inviting than your standard apartment block.

This is no mean feat given that the 77 apartments together contain 236 beds. And the word “collegial” is appropriate, because UC Berkeley signed a master lease with the developer and operates it as part of the student housing system.

Cozy turns captivating as you ascend.

Follow the bridges from one level to the next and it’s as if you’re inside a honeycomb. The higher you get, the more there is to see and do.

Two of the interior pods stop at three levels and are topped by communal terraces that get use throughout the day when studies and weather allow. One more level up, you encounter the startling contrast of panoramic views — and a dissected farm where you can touch the ground or snip off a sprig of parsley.

This time of year, between harvests, some pods show nothing but dirt. Others are softened by abundant mounds of green parsley and purple kale. One roof is dotted with red radishes waiting to be picked.

https://www.gardenvillageapt.com/

Garden Village is an award-winning 77-unit, furnished student housing and co-living complex located at 2201 Dwight Way. Built in 2016, the complex consists of 18 free-standing buildings connected by open-air walkways providing abundant natural light both inside and out. A fully operational commercial farm operates on the rooftop complex and is open to residents to visit, hang-out, or get involved. Stunning views across the bay are enjoyed from many vantage points. Outdoor and indoor spaces encourage community. Our units include both 2-bedroom and 4-bedroom configurations, with 1 bathroom per two bedrooms shared “jack-and-jill style”. Every bedroom has 9-foot ceilings and floor-to-ceiling windows allowing natural light. The units are fully stocked with all of the furniture and appliances that our residents may need. Interior finishes include wood cabinets, quartz countertops and backsplash, faux-wood plank vinyl flooring, combination tub/shower with quartz surround, porcelain pedestal sinks, both natural and efficient LED lighting.

Video:

Can Factory-Built Homes Help Solve The Housing Crisis?

CNBC News February 4, 2021 Video 10 minutes 25 seconds

The affordable housing crisis in the United States continues to be a problem and it’s only getting worse. And in places like San Francisco, where construction costs are some of the highest in the world, overcoming the housing shortage seems impossible. However, one solution is gaining traction that could dramatically reduce the cost and time to build new housing – factory-built apartments.

Oakland, California

Apartments Built on an Assembly Line

The pandemic put a general crimp in housing construction, but made a California factory that churns out prefabricated housing extra busy.

Factory OS is primarily focused on affordable housing — about 80 percent of what has been built here ranges from housing for the previously homeless to below-market-rate apartments for lower income workers, artists and students.

By Candace Jackson The New York Times

Published Sept. 10, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/10/realestate/prefabricated-modular-apartments.html

What if housing were built more like cars — on an assembly line in a factory?

Rick Holliday thinks it should be. The longtime Bay Area developer turned a former Naval submarine factory into one that has been doing exactly that. Workers at Factory OS construct apartment building components on Mare Island in Vallejo, Calif., about 40 miles from San Francisco, then transport them on flatbed trucks to their final location. “By the end of the process it goes out the door and it’s a fully formed apartment that you put together like Legos to form a completed building.”

The process can cut the time it takes to build an apartment building in half, to roughly only 11 to 12 months, he said, with multiple parts of construction taking place at once in a controlled environment, which means fewer delays and a more streamlined process in general.

Mr. Holliday, who co-founded the factory with Larry Pace, said doing it this way, versus constructing a building on site, also cuts costs by as much as 30 percent. In the Bay Area, where the price of building a single affordable housing unit is close to $1 million, it can mean the difference between a developer building an apartment or not.

“I got into the industry at 26 and building is no different than when I started,” said Mr. Holliday, 68. “If we don’t take a different approach to building, we’re not going to get anywhere.” So far, Factory OS has completed 10 buildings for a total of roughly 1,200 units in Northern California and gotten financial backing from tech companies like Google, Autodesk and Facebook.

A year and a half after opening its doors, the pandemic hit. Even as demand for housing accelerated, construction stalled. Prices skyrocketed for crucial materials like lumber, even further increasing the cost to build and worsening California’s affordability crisis, particularly in the already pricey Bay Area, where the median price for a single-family home now tops $1 million. Nationally, home prices were up a record 18 percent in July over the same month last year, according to data from CoreLogic.

Mr. Holliday said the upshot is that more developers in this staid, traditional industry have been willing to experiment in an attempt to cut costs and get projects done quickly. As a result: “We’ve been flooded with work.” Factory OS has expanded to add a second factory right behind the first. The company has 24 more projects in the pipeline and is planning to open a third factory in Los Angeles in the next two years to meet demand in Southern California.

They aren’t the only company trying to change how homes are built. IndieDwell, a three-year-old start-up based in Idaho, builds prefab, factory-built multifamily buildings, single-family homes and emergency housing. And there’s Blokable, a Sacramento-based company launched in 2016 to build and develop factory-built multifamily buildings. (Factory OS generally works with developers as customers, as opposed to developing and owning the buildings themselves.)

Stonly Blue, a San Francisco-based venture capitalist and an investor in Blokable, said a combination of factors from climate change to labor shortages have finally piqued the tech world’s interest in construction innovation. “The focus in recent decades has been software,” he said. “It’s slowly incrementing back to hardware and there’s nothing bigger and harder than buildings.”

Still, modular building is a concept that many have tried to innovate and failed at. Pulte Homes, one of the nation’s largest homebuilders, opened a prefab plant in the mid-2000s and then closed it in 2007 when the housing bubble burst. Katerra, a high-profile Silicon Valley-based prefab construction start-up that expanded very quickly and broadly, declared bankruptcy earlier this year. The company, which had factories in California, Washington and India, launched in 2015 and had $2 billion in funding and received a $200 million SoftBank cash infusion to try to save the business in December 2020.

“I have total confidence that this is the way forward, but it’s really hard to get right,” said Randy Miller, a co-founder of RAD Urban, a Bay Area-based modular construction company that went out of business earlier this year.

To begin with, setting up a factory isn’t cheap, and the challenges are numerous. Unlike general contractors, who have low fixed costs, modular builders have to continue to pay to operate a factory even when business slows down and during lulls in between projects. “You can’t just flip a switch and turn on a factory,” said Mr. Miller, who plans to launch another modular building company soon.

Factory OS’s approach is a 33-step process and, much like building a car, it starts with the chassis, or the underneath part of the apartment block, which is filled with pipes and ducts for plumbing and electrical work. On a recent morning, at least a hundred workers wearing hard hats and masks hammered and sanded away at several long, narrow shells of apartments laid lengthwise like railroad cars. (The factory is roughly the length of three football fields.) It was a loud and dusty scene, but also orderly and efficient.

Some workers fit piping underneath a boxlike structure raised up on a rack so they could more easily reach low areas than at a typical construction site, where they would have to crouch underneath. Nearby, there were arms that could rotate the structures for easy access as well. On another side of the factory, neatly arranged components — from tubing to insulation to kitchen cabinets — sat on shelves. It looked like a very specific Home Depot display.

Factory OS is primarily focused on affordable housing — about 80 percent of what has been built here ranges from housing for the previously homeless to below-market-rate apartments for lower income workers, artists and students. The company takes on a handful of market rate and luxury projects too, but in the past three to five months, there has been so much demand that Mr. Holliday said he has had to turn away business.

Toward Factory OS’s entrance, a completed model apartment unit stood like a large box visitors could walk inside. The 25-foot by 12-foot studio had sturdy vinyl flooring, a two-burner stove, built-in kitchen cabinets and a stainless steel fridge. Behind a farmhouse-style sliding door there was a decent-sized bathroom. A gray Ikea couch in the living room could convert to a bed.

Mr. Holliday explained that the unit was similar to ones they built in a complex in Oakland to house previously homeless tenants. Two of these apartments plus the hallway space between them can travel on the same truck.

Mr. Holliday said one of his big challenges is finding enough workers to meet demand. “The labor force for building housing is shrinking,” he said. His solution? Hire and train people who may not otherwise find employment. About half of Factory OS’s unionized employees are “second chance” workers, including about 20 percent who have served time in prison.

The pandemic has also exposed another downside of factory construction: Workers are in relatively close contact indoors. Factory OS now has a requirement that all employees get vaccinated by the end of September.

Though building facades can be customized, floor plans in factory-built homes need to be uniform. Every studio apartment, for example, needs to have the same layout to maximize efficiency in modular building. Mr. Holliday said he didn’t think that should stand in the way of building the housing we need, comparing the innovation of modular housing to the suburban standardization in Levittown, N.Y., which kicked off the construction of many of America’s suburbs to house young families after World War II. “We’ve allowed the design of buildings to get too complicated,” he said.

In the near future, the goal is to further streamline the process by creating even more standardized floor plans and designs that developer clients could basically pick from a catalog. Factory OS has partnered with Autodesk, a company that makes software for engineers and architects, to make interactive building plans that could guide workers as they go along, almost like a Google Maps version of an architectural drawing. It would also layer data findings from previous projects to maximize efficiency.

To avoid the fate of companies that have expanded too quickly, Mr. Holliday said he planned to keep his business a West Coast operation. “My hope is that we become a stimulant for the industry,” Mr. Holliday said. “Not that we set up a lot of factories ourselves.”

Factory_OS website https://factoryos.com/

20% – 40% less expensive

40% – 50% faster

500+ locals trained & employed

Factory OS is revolutionizing home construction. We’ve combined pioneering technology with tried-and-true manufacturing methods to build multifamily modular buildings more efficiently and at a lower cost. We’re building more affordable homes, creating good local jobs, and funding innovation.

We’re not just building homes.

We are manufacturing the future.

San Francisco, California

A new S.F. housing complex for homeless people was faster, cheaper to build. So why isn’t it being replicated?

The project began when Charles and Helen Schwab contributed $65 million to Tipping Point for its initiative to stem chronic homelessness.

by Heather Knight San Francisco Chronicle

Feb. 2, 2022

See also:

Give Them Shelter: Want to solve America’s urban homeless crisis? First, you have to believe it can be fixed. April 6, 2021. Stanford School of Business alumni news. Rebecca Foster, MBA ’05 and Liz Givens, MBA ’04, created the six-story building with 145 affordable, modular homes.

Tahanan Supportive Housing– David Baker Architects website. With floor plans and many photos.

He slept in the airport. He slept in a tent under the Bay Bridge. He slept in homeless shelters. He slept in a dirty, run-down Single Room Occupancy hotel in the Tenderloin where the communal bathroom wasn’t big enough to accommodate his wheelchair and the elevator regularly broke down, stranding him.

Two months ago, Timothy Isaiah, 57, finally moved into his own apartment. He has a large, private bathroom and a small kitchen. The two elevators work. The facility is bright, clean and secure. At first, Isaiah was so excited, he couldn’t sleep.

“I couldn’t believe it was happening to me,” he said, beaming as he pet his chihuahua, Kelly. “I couldn’t ask for a better place.”

And San Francisco couldn’t ask for one, either. Isaiah is one of 145 formerly homeless tenants who’ve just moved into 833 Bryant St. The permanent supportive housing complex — called Tahanan, which means home in Tagalog — was built in three years, and construction costs were $385,000 per unit.

In this incredibly expensive, bureaucratic city, affordable housing usually takes five to seven years to build, though a full decade isn’t unheard of. And it usually costs at least $600,000 per small studio like Isaiah’s and far more for larger units.

Housing Isaiah and his new neighbors is one huge plus for Tahanan. But its larger point was to serve as a testing ground to see if it was possible to build affordable housing for less money and in less time than normal. The experiment worked, but so far there’s no firm plan to replicate it — even with San Francisco’s huge homelessness crisis and a desperate need for many more Tahanans.

That makes Sam Cobb, CEO of Tipping Point, the anti-poverty philanthropic nonprofit that launched the Tahanan experiment, angry.

“It’s beyond frustrating,” Cobb said of the city’s slow response to housing unsheltered people. “I’m pissed off and heartbroken.

“This building has done what it was supposed to do,” he continued. “The pipeline should be full of units and buildings just like this but, unfortunately, that’s not the way it works in San Francisco.”

The project began when Charles and Helen Schwab contributed $65 million to Tipping Point for its initiative to stem chronic homelessness. Tipping Point teamed with the San Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund, which raises private and public money to build affordable housing, to manage the experiment at 833 Bryant using $50 million of the Schwab money.

From there, many dominoes began to fall into place. The fund purchased a parking lot across the street from the city’s hulking Hall of Justice in 2018 for about $8 million in cash and helped craft a city zoning change allowing 100% affordable housing to be built on some South of Market parking lots.

The project also benefited from state Sen. Scott Wiener’s SB35, the 2017 state law that provides streamlined permitting for some affordable housing projects. Nonprofit Mercy Housing worked as the developer and now owns and operates the building, and Episcopal Community Services is providing services to tenants. The city is paying the costs of operating the building and providing services.

Another big key to making Tahanan less expensive and faster to build is that it’s composed of modular units crafted at a factory in Vallejo, trucked over the Bay Bridge and assembled like a big Lego project. The factory is unionized, but San Francisco building and trades groups don’t like the building method because it leaves them out. That’s prompted many members of the Board of Supervisors to be leery about approving future modular projects, although a few other ones are in the works, all affordable buildings.

Rebecca Foster, CEO of the Housing Accelerator Fund, said the real key to building Tahanan so quickly was “total clarity” for everybody involved — from the architects to the developer to the general contractor — that the goal was to build the units in three years or fewer and for less than $400,000 per unit.

Having all those pieces come together for a second time has so far proved elusive. Foster said a big reason is that 833 Bryant was built on private land with private money. If it had city funding up front or was built on city land, it would have faced a gauntlet of approvals adding far more time and cost.

“It’s sort of death by a thousand cuts,” said Foster, who supports Mayor London Breed’s efforts to streamline the construction of affordable housing projects, an effort quashed for the third time in a Board of Supervisors committee last week.

Supervisors Aaron Peskin and Connie Chan tabled the Charter amendment, saying it hadn’t been vetted properly with community stakeholders. Neither returned a request for comment on Tuesday. Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, who didn’t vote to table the amendment but wasn’t wild about it, either, said Tuesday the mayor’s plan was too complicated.

So the idea to make the construction of affordable housing less complicated was in itself too complicated. How very San Francisco.

“I do think we need to find ways to streamline our approvals,” Mandelman said. “We should describe what we want in our zoning and then get out of the way and let people do it.”

That’s an idea supported by Foster, who said she thinks San Francisco should create a housing challenge in which it vows the city will pay the operating and services costs for permanent supportive housing projects that can be built quickly and cheaply. She pointed out that Prop. C money from the city’s biggest businesses to pay for homeless housing and services could fund it.

The huge Schwab gift gave her fund the confidence to proceed with the 833 Bryant St. project even without the city support that eventually came through to pay for operations and services, but she said that’s “a once in a lifetime opportunity” that most housing developers won’t have. The remaining Schwab money helped purchase two coronavirus shelter-in-place hotels to turn them into housing.

Whatever it takes to create more Tahanans, it should happen fast so more people can know the joy and relief of moving off the streets or out of run-down Single Room Occupancy hotels.

Isaiah showed me a courtyard behind his new home that’s painted in pastel arcs and features a fountain, plants and benches. It’s a dream, he said, whereas his SRO hotel was his “worst nightmare.”

He was paralyzed from the waist down after suffering two strokes and could only take a sponge bath there because the communal shower was so small. He had to call the fire department a few times to carry him downstairs for doctor’s appointments when the elevator failed. Drug paraphernalia littered the hallways, and threatening people walked in and out, he said.

At Tahanan, it’s totally different. The atmosphere is quiet and soothing. The building has regular coffee and doughnut get-togethers, gives away free sacks of food and has nurses and caseworkers on site. Every entrance is secured and monitored.

“This place is a blessing,” Isaiah said. “I’m a survivor, and I made it.”

San Francisco, California

Modular housing could be an answer to state housing crisis

Modules can be assembled into apartment buildings 40% more quickly and 20% cheaper than traditional construction

by Dan Walters published in the San Jose Mercury News

March 31, 2021

https://www.mercurynews.com/2021/03/31/walters-modular-housing-could-be-an-answer-to-state-housing-crisis/

Two years ago, CalMatters housing writer Matt Levin described a factory in Vallejo that was building housing modules that could quickly — and relatively inexpensively — be assembled into multi-story apartment houses.

Levin described the factory as more resembling an automobile assembly line than a construction site. “They build one floor approximately every two and a half hours,” Larry Pace, co-founder of Factory OS, told Levin. “It’s fast.”

Modular construction offers a potential solution to one of the most vexing aspects of California’s housing crisis — the extremely high costs of building apartments meant to house low- and moderate-income families.

Statewide, those costs average about $500,000 a unit, encompassing land costs, governmental red tape, ever-rising prices for materials and, finally, wages for unionized workers who build, plumb and electrify the apartments.

“Further inside the massive Vallejo plant, there’s a station for cabinets, a station for roofing and a station for plumbing and electrical wiring,” Levin wrote. “Station 33 looks like a furniture showroom not quite ready for the floor — washer, dryer and microwave included.

“From there the apartment pieces are wrapped and trucked to the construction site, where they’re assembled in a matter of days, not months.”

Pace said that his modules can be assembled into three- to five-story apartment buildings 40% more quickly and 20% less expensively than traditional construction, which means more bang for the buck.

Today, a Factory OS apartment house for 145 hitherto homeless residents is being assembled in downtown San Francisco in what appears to be proof of what Pace told Levin.

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Heather Knight described the project in a recent article, saying, “The project at 833 Bryant St. is being built faster and cheaper than the typical affordable housing development in San Francisco, the ones that notoriously drag on for six years or more and cost an average of $700,000 per unit. This project will take just three years and clock in at $383,000 per unit.”

In other words, by using modular construction San Francisco could supply twice as many units for the same money. So what’s not to like? Knight tells us what.

“At issue,” she writes, “is how the project was built so quickly: with modular units made in a Vallejo factory. Each unit was trucked across the Bay Bridge, strung from a crane and locked in place like a giant Lego creation. San Francisco unions don’t like the method because it leaves them out, but considering the city’s extreme homelessness crisis, City Hall can’t afford to toss the idea.”

Factory OS uses unionized workers, but through an agreement with the carpenters’ union, workers perform a variety of tasks on the housing assembly line, rather than having the work divvied up among specialists, and the company employs many former prison inmates.

Politically influential construction trades unions are pushing San Francisco’s city officials to make 833 Bryant St. a one-time event rather than the beginning of a trend.

Larry Mazzola Jr., president of the San Francisco Building and Construction Trades Council, is sending a letter to Mayor London Breed and city supervisors criticizing the project’s “mistakes and over-costs.”

“The quality is crap, to put it basically,” Mazzola told Knight “They don’t have plumbers doing the plumbing. They don’t have electricians doing electrical. They get them from San Quentin, and they’re not trained at all. We’re going to fight vigorously with the city not to do any more of these.”

Modular housing is not a panacea for California’s housing woes, but it deals with one major factor. The question is whether politicians will embrace it or strangle it.

Medford prefabricated apartment complex to address housing shortage for fire victims

by Malik Patterson News 10 – Medford

March 31st 2022

Medford, Ore. — Oregon Housing and Community Services has approved a plan to begin construction this summer on a prefabricated modular apartment complex north of Medford to house victims of the 2020 Labor Day fires.

Designed by Portland real estate developer Project^, the 9 sleek, modern apartment buildings, each with 5 floors of units, is known as MOSAIC.

“If you are connected to the Labor Day or Almeda fire relief and you are in the workforce then those households will be prioritized to you first,” said Jonathon Ledesma, project manager.

According to Oregon Public Broadcasting, funding for MOSAIC comes in part from a state allocation of $150 million for wildfire housing recovery from the $600 million assistance package passed in July 2021. To build MOSAIC, OHCS loaned $10 million to Project^ at 0% interest for the first 2 years and then 1% after.

Project^ will also manage the 148 units’ construction, starting with fabricating the buildings’ interiors in a factory, then trucking them to the 7.5 acre plot formerly owned by Ivanko Gardens Apartments.

The prefabricated portions of the buildings will be made at Intelifab, a Klamath Falls factory, and are “pretty much ready to go,” Ledesma said, “meaning the finishes are all in, cabinets, toilets appliances.”

While other housing relief programs are designed to serve low-income fire victims, this project targets the Rogue Valley’s middle-income earners, many of which still struggle to find housing amid this area’s low-inventory and high prices.

Project^ said they’ll be accepting rental applications from people making 80-120% of Medford’s average median income. For a family, this would be between $58,449.60 to $87,674.40 a year.

OHCS said fire survivors will have several different loan options to mortgage their unit.

The project is expected to be completed by July 2023.

Prefab housing complex for UC Berkeley students goes up in four days

A four-story apartment building destined to house grad students went up in four days in July, including beds, sinks, sofas, and stoves.

August 2, 2018

Imagine a four-story apartment building going up in four days, and from steel.

It happened in Berkeley, a city known for its glacial progress in building housing.

Check out 2711 Shattuck Ave. near downtown Berkeley. Four stories. Four days in July. Including beds, sinks, sofas, and stoves.

How?

This new 22-unit project from local developer Patrick Kennedy (Panoramic Interests) is the first in the nation to be constructed of prefabricated all-steel modular units made in China. Each module, which looks a little like sleekly designed shipping containers with picture windows on one end, is stacked on another like giant Legos.

The project, initially approved by the city in 2010 as a hotel, then re-approved in 2015 as studio apartments, will be leased to UC Berkeley for graduate student housing. Called Shattuck Studios, it’s slated to be open for move-in for the fall semester.

“This is the first steel modular project from China in America,” Kennedy said, adding that new tariffs on imported Chinese steel hadn’t affected this project.

The modules were shipped to Oakland then trucked to the site. Kennedy notes that the cost of trucking to Berkeley from the port of Oakland was more expensive than the cost of shipping from Hong Kong.

The modules are effectively ready-to-go 310-square-feet studio apartments with a bathroom, closets, a front entry area, and a main room with a kitchenette and sofa that converts to a queen-size bed. They come with flat-screen TVs and coffee makers.

“In order to be feasible, modular construction requires standardized unit sizes and design, and economies of scale,” Kennedy said.

The complex has no car parking, but 22 bicycle parking spots. It has no elevator, and no interior common rooms except hallways, but has a shared outdoor patio/BBQ area. ADA accessible units are on the ground floor.

Floors in each unit are bamboo and tile. The appliances are stainless steel. The bathroom has an over-sized shower. The entry room has a “gear wall” for hanging backpacks, skateboards, bike helmets. Colors are grays and beiges and light browns.

“Our units reflect the more austere, minimalist NorCal sensibility,” Kennedy said, during a recent tour of the complex. “Less but better.”

The modules were stacked on a conventional foundation. Electricity, plumbing, the roof, landscaping and other infrastructure were added.

Using prefab material is supposed to be less expensive than building from scratch, Kennedy said. He had anticipated significantly lower costs by going prefab for this project.

But the savings haven’t been as great as expected, he said. “Sixty-five to seventy-five-percent of the construction costs are still incurred on the site. In addition to the usual trades, we have crane operators, flagmen, truckers and special inspectors.”

He’s still evaluating bottom-line costs.

“We are very happy with the quality of construction and the finished product — but we learned that smaller sites posed lots of difficulties — access, traffic management, proximity to neighbors,” said Kennedy who works with Pankow Builders of Oakland. “We might have saved some money building this conventionally, but we view this more as a research & development project — and in that capacity, it was very helpful and educating.”

Prefab construction probably makes more financial sense with larger projects (more units) on larger lots, Kennedy said. “If you don’t have space to work it gets very expensive very quickly.”

The goal — and hope — is that prefab will open the door to more affordable housing through lower construction costs. “We’re still trying to determine the optimal size. It’s a pretty new idea here in Northern California. We are learning as we go,” he said.

Kennedy said he knows of a few locations in the West Coast that sell similar modules, but they’re backlogged by years. So he went overseas. “The industry is evolving rapidly, and we are always looking to bring down costs. . . We would love to use local firms.” He built one previous prefab apartment project in San Francisco with a Sacramento manufacturer who is now out of business.

In lieu of providing affordable units on site, Kennedy will pay a fee to the city of Berkeley’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund, as required under the city’s affordable housing laws. The amount is around $500,000, he said.

In a few weeks, roughly four months from the start of construction, nearly two dozen UC Berkeley graduate students should be moving into the complex.

The units will rent for $2,180 monthly for single-occupancy, said Kyle Gibson, director of communications for UC Berkeley Capital Strategies. One unit is reserved for a residential assistant (RA). UC has a three-year lease with Kennedy’s firm.

Panoramic Interests will do building maintenance and cleaning.

Gibson said the university wasn’t involved in the design or construction, and he had no comment on the prefab approach. The project is one of several new developments recently completed or in the pipeline to increase student housing, he said. Some are university-built and owned, others leased.

“The University welcomes any and all projects and developments that expand the availability of affordable, accessible student housing in close proximity to campus,” Gibson said.

“It’s been an incredibly valuable tutorial for us. We know prefab is going to be the future, we just don’t know how we’re going to be part of it,” Kennedy said. “I’m chastened by the complexity of doing something so seemingly simple as stacking boxes on top of each other.”

Oakland, California – Coliseum Connections

Coliseum Connections is a 110 unit half-affordable, half-market rate, transit village development located next to the Coliseum BART station in Oakland, California.

There are 179 modules here, to make 110 apartments.

The completed project is comprised of four buildings:

- A five-story building accommodating 66 one- and two- bedroom flats

- Three buildings with 44 total two-story town-homes.

The main building utilizes a hybrid first floor with 2,200 square feet of site built retail space and 10 prefab built apartments. Floors 2 through 5 each have 14 apartments of type 3 modular construction fabricated in Guerdon’s Boise, Idaho facility.

The developer selected modular construction for this project to save both time and money. The project realized a 20-25% time savings over estimates for traditional site-built methods, opening in 16 months, 4 months faster than the estimated 20 months required for site built. The developer also saw an estimated 10% savings in overall construction costs, which on a $40 million project works out to close to a $4 million savings.

This project has the goal of achieving GreenPoint Rated Silver certification, in addition to the green benefits inherent with modular construction.

Privately owned, public access pedestrian walkway

The project includes development of a 25-foot wide pedestrian mews bordering the east edge of the project. This landscaped mews will link 70th and 71st Street, providing neighbors with a direct walking and biking path to the Coliseum Station. This mews is private, but will allow access at all times through a public access easement.

https://www.rcmgroupe.com/en/achievements/2-apartments-and-condominiums.php

Multistory apartment St. Beverly, MA

– Building A Number of stories: 6

Number of modules: 134 Number of dwelling units: 76

Factory production time: 9 weeks On-site assembly time: 7 weeks

– Building B Number of stories: 5

Number of modules: 40 Number of dwelling units: 28

Factory production time: 4 weeks On-site assembly time: 2 weeks

Number of stories: 3

Number of modules: 57 Number of dwelling units: 36

Factory production time: 6 weeks On-site assembly time: 12 weeks

This is the first of three buildings being built on the same site. The first building is for low-income clients, the second has standard apartments, and the third is a building for seniors.

Additional links:

The modular revolution promises to shake up Bay Area housing

February 16, 2018

RAD Urban completed a 43-unit modular apartment building at 4801 Shattuck Ave. in Oakland.