“The thirteen thousand tons of food waste produced daily in South Korea now become one of three things:

Compost – 30%

Animal feed – 60%

Biofuel – 10%

Perhaps require new construction to accommodate or have collection services for food-waste — as is done in Korea currently.

South Korea recycles ninety-five per cent of its food waste. New York City: 5%.

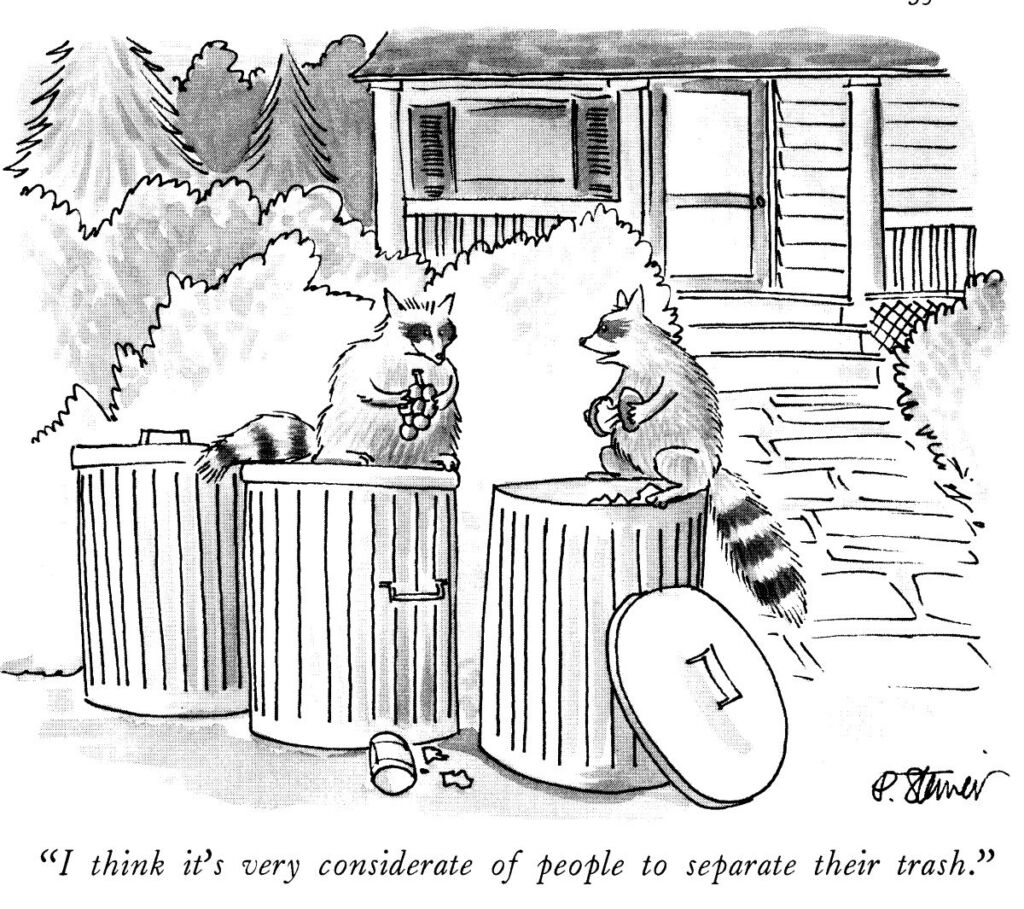

See this article from The New Yorker:

How South Korea Is Composting Its Way to Sustainability

Automated bins, rooftop farms, and underground mushroom-growing help clean up the mess.

By Rivka Galchen March 2, 2020

In 1995, South Korea replaced its flat tax for waste disposal with a new system. Recycling materials were picked up free of charge, but for all other trash the city imposed a fee, which was calculated by measuring the size and number of bags. By 2006, it was illegal to send food waste to landfills and dumps; citizens were required to separate it out. The new waste policies were supported with grants to the then nascent recycling industry. These measures have led to a decrease in food waste, per person, of about three-quarters of a pound a day—the weight of a Big Mac and fries, or a couple of grapefruits. The country estimates the economic benefit of these policies to be, over the years, in the billions of dollars.

Residents of Seoul can buy designated biodegradable bags for their food scraps, which are disposed of in automated bins, usually situated in an apartment building’s parking area. The bins weigh and charge per kilogram of organic waste.”

The thirteen thousand tons of food waste produced daily in South Korea now become one of three things: compost (thirty per cent), animal feed (sixty per cent), or biofuel (ten per cent). “People from other countries ask me very often, ‘How did South Korea achieve this success?’ ” Kim said. Sometimes it is attributed to the fancy technology that weighs and tracks the compost, and to the R.F.I.D. chips used in some municipalities to insure that households pay in proportion to the amount of waste they produce. “That is important,” she told me. “But also I say the government shouldn’t act directly. There needs to be an intermediary between the government and the people. Groups like us. That can explain back and forth. People don’t want to hear it straight from the government.” Setting up waste-processing sites was difficult, in part because there were fears that such sites would become sources of stink or disease, like the landfills. “We went door to door to talk to residents. We would bring people in for a tour of the food-waste facility. We would educate people about how it was healthy. I’ve been shouted at a lot,” Kim said, laughing. “But things change. People are used to it now. These days, we focus on offering seminars at local centers, or wherever people gather.” She added, “We have the most difficulty in wealthy neighborhoods and neighborhoods with foreigners.”