Estimated reading and viewing time: 5 minutes

See also Lessons from a Modern Master of Low-Rise Housing

Density does not require height

This article is part of an on-going series here on Arcata1.com on what makes for a livable city, and what we here in Arcata can learn from urban planning designs in other locations and from other eras. I am not proposing that we can directly copy these other projects — only that we can have much to learn from them.

Arcata at this time has its own unique set of issues and criteria. Other cities and towns — big and small, both recently and in the past — have had the similar need to provide housing within a limited space. Life in America included plenty of what we can call automobile-oriented sprawl, with suburbs constructed over level farmland all over the place. But we should not forget or ignore that there has been dense, in-fill development that’s taken place too, in cities all over the world, pretty much since the beginning of civilization.

The design shown here is in a dense urban environment. A design here in Arcata would (hopefully) have more of the parcel open and green, for open space for all people of the city to appreciate.

To repeat: I am not saying to copy this example. I am saying: We can learn from this.

Louis Sauer, Architect

The attached townhouse is a desperately needed style of housing.

Townhomes in the U.S. largely fail to achieve any decent design.

The architect Louis Sauer specialized in high-quality, high-density, low rise housing. His urban designs were typically just three stories tall, with configurations of intertwined townhomes, set in patterns so that each home had a separate and private yard.

The attached townhouse is a desperately needed style of housing. Townhomes in the U.S. largely fail to achieve any decent design.

Sauer built dozens of modernist-style housing projects in cities in the US Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states in the 1960s and 1970s, winning six Progressive Architecture Awards. His projects were imaginative and livable.

His work included low-income minority projects, where he advocated for improved design and planning for people left out of the market economy and generally otherwise neglected by mainstream design professionals, including people with physical challenges. This interest led him to utilize the social sciences in his design research to better understand the interrelationships between architecture and the occupancy needs of the actual people who live in his buildings.

Sauer believed that unless architectural schools figured out how to teach students to design for increased building performance and to deal with society on realistic economic terms, society would rely more on engineers and bureaucrats to provide inferior social design.

His design for Penn’s Landing Square in Center City Philadelphia from 1970 is shown here. He had one entire city block for redevelopment. The block is 400 feet by 250 feet, or 2.3 acres; the block in Arcata is 250 by 250, or 1.44 acres. So he is working with 1.6 Arcata-sized blocks.

In this area he put 54 townhomes of three stories, with the third story being an independent unit with a ground-floor entrance and dedicated stairs. There were both condominium and rental units, for a total of 118 housing units (~ 174 inhabitants) and a density of 45 units per acre. The units are 750 to 815 square feet for a large one-bedroom (what we might have be a two-bedroom apartment) up to 1,650 sq.ft. for a three-bedroom unit.

It is important to note that even with a 45 unit per acre density, this design is not a block-shaped or monolithic apartment house. Each unit has its own individual private open space. The upper-stories are built with deep step-backs, to make for an open patio space on the roof of the lower floor — patios of about 13 feet by 19 feet. In other words, not just a narrow deck space, such as we regularly see here in Arcata, but a large useable outdoor space. Ground floor patio open space is in addition to the deck space.

All parking is underground. (This is located in a very built-up large urban city, where ground space is precious. Underground parking is fairly common.)

His designs tended toward buildings that were shaped as an L, T, or Z, so that the patterns formed would provide for the private outdoor patios, with one courtyard to back and another courtyard to the front, while ensuring plenty of light.

The block-size design for Penn’s Landing Square, Philadelphia. Approximately 45 units per acre. The buildings are three stories around the perimeter and two stories in the interior. Every unit has a private outdoor open space.

In this aerial image, the white spaces (except for a few rooftops) are the public area. A pool is seen at the upper right. The pinkish spaces are patios — see below.

The white rectangles are patios for upper-floor apartments that are essentially an open space formed from the step-backs of the lower stories. Note how the developer did not build all the way out to the corner at the upper left, as a cut-away for a small public plaza area.

The white rectangles are patios for upper-floor apartments that are essentially an open space formed from the step-backs of the lower stories. Note how the developer did not build all the way out to the corner at the upper left, as a cut-away for a small public plaza area.

The upper-floor patio. The view includes the previously-existing three-story plus attic homes on the other side of the street from Penn’s Landing Square.

Density without height. Note the sloped rooflines of the buildings along three sides of the perimeter — sloping toward the interior for longer sight-lines to the edge of a roof for the interior inhabitants, and a more expansive feeling.

Penn’s Landing Square, in the foreground.

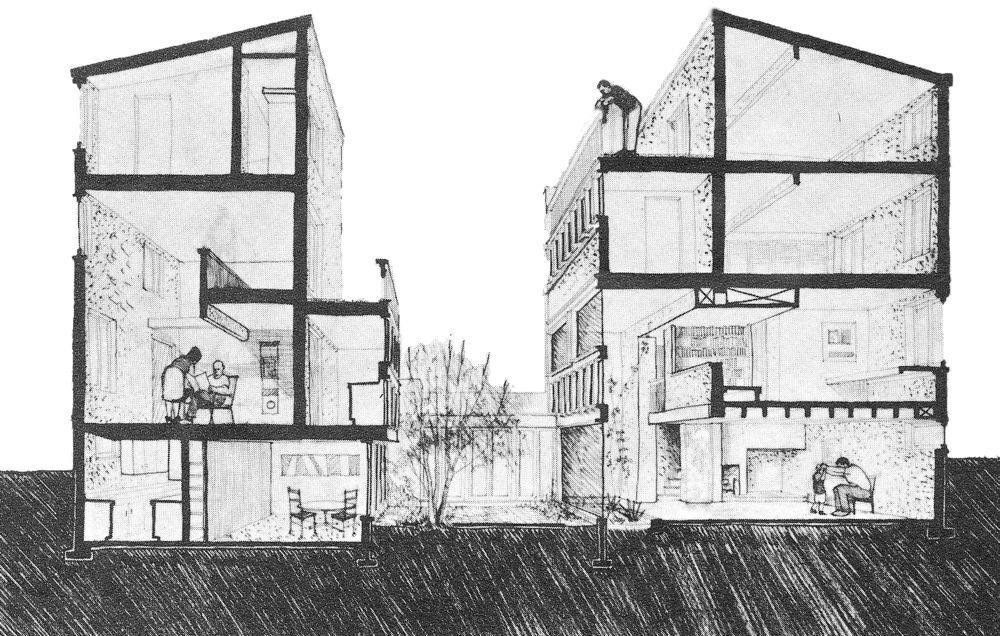

This is not Penn’s Landing Square, but a different Louis Sauer urban townhouse design. Here there is a lower basement level. Again there the is the patio-depth step-back on the 2nd (left side) and 3rd (right side) for private outdoor open space and for more light and sky to the central patio.