For more on the dorm room conundrum, see:

Windowless bedrooms? Sunlight is considered a luxury benefit

Cal Poly Humboldt – Expansion

Cal Poly Humboldt projected 2,000 more students for Fall. Actual enrollment increase: 98

The EIR for the Craftsman Mall dorm project at Cal Poly: Craftsman Dorms

Is this parallel to our situation in Arcata?

This Wall Street Journal article discusses the student housing situation at Clemson University, in Clemson, South Carolina.

This Wall Street Journal article discusses the student housing situation at Clemson University, in Clemson, South Carolina.

Basically, it tells us what we already knew: Universities all over, whether here in Arcata or in South Carolina, are supplying about one-third of the housing that they need. For the rest of it, they rely on private developers to build student housing to make up the shortfall.

There are many differences between Clemson University and Cal Poly Humboldt and the “town and gown” relationships. In terms of the lack of student housing as provided by the university and the rising cost of housing, there are lots of similarities.

Cal Poly Humboldt (CPH) has university-supplied housing for about one-third of its students. The projected figures are to add about 2,050 – 2,250 dorm beds over the next 8 years. The new Craftsman Mall dorms, with the six-story and seven-story towers, are 940 beds.

If the enrollment at CPH goes up by 5,500 or 6,000, then the new housing will take care of about one-third of increased enrollment — the same as the current ratio.

Clemson dorms and private housing

At Clemson, the university added nearly 1,500 beds since 2013, while its population increased by more than 5,700 students. Private builders added at least 3,600 beds near campus in five years between 2014 and 2019.

Clemson University has about 29,000 students. The official population of the city of Clemson is only 18,000. Clemson University is actually a separate municipality. “The fact that they are a completely separate municipality does not require them to consult, cooperate or approve anything with the city,” said Todd Steadman, director of planning and codes for the city of Clemson. Just as Cal Poly Humboldt is independent from the City of Arcata, Clemson does not have to follow city ordinances or approval processes.

Clemson University vs. Cal Poly Humboldt

Cal Poly Humboldt’s current enrollment is about 6,000 students — and this is projected to double to over 12,000 students within six years. The City of Arcata has a current population of about 20,000.

Clemson’s freshman retention rate is 94%, with 85.5% going on to graduate within six years. Cal Poly Humboldt’s rates are more than 25 percentage points lower — but that could be because more students transfer from CPH to other universities and not because they drop out.

Cal Poly Humboldt’s freshman retention rate is 73%, which places it in the middle of California universities and colleges and slightly above the middle for the U.S. The six-year graduation rate is 58%. About 27% students transfer and 12% drop out.

Clemson’s in-state tuition and fees are $15,558. Out-of-state tuition and fees are $38,500. An on-campus rooms is $7,800, and meals are $4,400. For students receiving financial aid, the average cost after financial aid is shown at $23,000. 99% of all students receive financial aid, averaging $9,670.

Cal Poly Humboldt’s in-state tuition and fees are $7,900. Out-of-state tuition and fees are $19,755. An on-campus rooms is $6,600, and meals are $5,600. For students receiving financial aid, the average cost after financial aid is shown at $16,000. 77% of all students receive financial aid, averaging $9,650.

Below is the article from the Wall Street Journal. For more on the windowless dorm room controversy, see Windowless bedrooms? Sunlight is considered a luxury benefit.

Windowless Rooms and Town-Gown Battles: How Student Housing Got Expensive

Investors like student apartments because returns are steady and tenants can borrow to pay the rent

By Shane Shifflett for the Wall Street Journal

Updated March 25, 2024

Clemson University didn’t have enough dorms on campus for its students. Private developers—including the family of the school’s president—are stepping in.

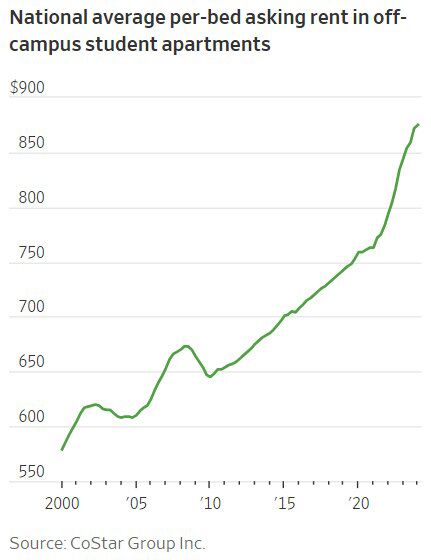

Student housing has emerged as a hot sector in real estate. But high rents are squeezing students, forcing some to take on more debt, and others to choose windowless rooms in expensive cities like Austin, Texas. A room with no natural light in a four-bedroom apartment there now costs $1,300 a month. These are often the cheapest, and most popular, off-campus options in some properties.

The large public universities analyzed by both the Journal and Moody’s Analytics had fewer than 613,000 beds last year to house a combined full-time undergraduate population of 1.8 million. The schools added fewer than 8,000 beds between 2019 and 2023, while private firms added more than 44,600 beds.

Investors like student housing in part because students can borrow to cover the rent. “Students can take out loans for housing,” said Shangxuan Tan, chief executive of Chicago-based private-equity firm OC Ventures, in an investor presentation viewed by the Journal. The firm buys and sells student-housing properties. “There is never a bad time to invest in student housing,” he added.

The boom in private student housing has set off fights in communities surrounding campuses that have been overwhelmed with private developments. At least five have moved to temporarily ban or regulate student apartments.

In 2020, Clemson, S.C., blocked new development, worried that towers being built were changing the character of the small town. The family of the president, James Clements, later sued several City Council members for the right to develop their property. The case is pending.

Clemson City Council member Catherine Watt said if the school wants to grow, it needs to house its students. “We don’t have the space or infrastructure to manage their growth,” she said. Since 2019, rents in Clemson have risen faster than almost anywhere in the nation, according to data from Moody’s Analytics.

[The graphic on the right shows the increase in the number of students — and how the increase in the number of dorm beds is not keeping up.]

The university added nearly 1,500 beds since 2013, while its population increased by more than 5,700 students, data show. Private builders added at least 3,600 beds near campus between 2014 and 2019, according to a Journal review of property records.

The university spent in other areas, including a $64 million refresh of a basketball arena using athletic department revenue and a nearly $90 million building for the College of Business partially funded by donors.

The school says it is keeping the student population steady despite record applications and is starting a new master plan for housing. The university and Clements aren’t involved with the president’s relatives’ project, a Clemson spokesman said. An attorney for the investors said they can’t comment due to ongoing litigation.

Student housing developer Fountain Residential got approval for a $75 million, 633-bed luxury apartment complex called Dockside, which was one of the last projects to get the go-ahead as the ban took effect.

“The demand is for better housing,” the company’s CEO Brent Little, said in an email. “This is what is driving rental rates up—the demand for the better product.” The company intends to list the property for sale later this year with a targeted price above $100 million, he said.

Housing costs for students living on campus also soared over the past two decades, a Journal investigation shows, with several universities turning to private companies to develop new dorms.

The skyrocketing value of student apartments is attracting big investors. More than 40% of last year’s buyers were big U.S. or foreign investors, MSCI data show. “Where is capital going in the commercial real-estate space?” said CoStar analyst Chad Littell. “It’s following rent growth, and student housing is showing some of the strongest rent growth.”

In 2022, private-equity firm Blackstone paid $13 billion to acquire American Campus Communities, one of the first and largest student-housing landlords. A Blackstone spokeswoman said the firm invests in areas with strong demand and seeks to provide a good experience for renters.

Austin, Texas, until recently the nation’s hottest housing market, has been lucrative for student-housing landlords. It also has the dubious distinction of renting more than 1,000 windowless rooms to students at high prices, according to a tally by a University of Texas professor.

In its purchase of American Campus Communities, Blackstone picked up a 343-bed apartment building known as the Crest at Pearl in Austin. Rents had already soared there, with rents for a windowless room in a four-bedroom unit increasing by 25% between 2016 and 2024 to nearly $1,300, the Journal’s analysis shows.

About 10% of the bedrooms in the Crest are windowless. A bed in one of the windowless units can cost as much as $1,500 for the fall 2024 school year.

“The solution to rising costs is more supply, and we are incredibly proud to have developed hundreds of beds and invested tens of millions of dollars to add to and improve Austin’s student housing inventory,” an American Campus Communities spokeswoman said. The company invested nearly $3 million in improving the property, she said.

Windowless rooms became an issue in Austin after students said living without natural light affected their health. Some students campaigned against windowless rooms and UT Austin professor Juan Miró pressed for the city to update Austin’s building code to require access to natural light in bedrooms.

Last year, Austin’s City Council approved a resolution requiring all bedrooms in new buildings to have access to natural light.

High rents have pressured students to take these rooms. For two years, biology major Breanna Ellis paid about $1,000 a month for a windowless room in a building called Lark Austin. She graduated with $20,000 in debt in 2021 despite working part time and receiving a scholarship covering tuition.

“At first it didn’t really bother me that it didn’t have a window,” Ellis said. “I would joke about it but at one point it didn’t feel good…it was a dark cave.” She bought a clock to hang on the wall of the mostly gray room so she could tell the time of day and a friend’s mom gave her a mirror decorated with window panes.

During her senior year, Ellis sought mental-health treatment for a variety of reasons including what she said was the strain of living in a sunless room. She was prescribed antidepressants.

The Lark is owned by real-estate firm The Scion Group, one of the biggest student landlords, managing nearly 83,000 beds. The company charges $30 extra a month for a window in a bedroom on top of a $55 monthly amenity fee.

“While this young lady’s circumstance is unfortunate, those units are the most popular and the fastest to lease,” said Scion Group President Rob Bronstein. “Her peers are voting with their dollars, and they are choosing the least expensive options first.”