“If you design better public spaces, you change the relationship residents have with a city, and also with each other.”

What happens when an expert in building public spaces is given the reins of a European capital?

When the mayor is an architect, a civic activist, and an advocate for fewer cars and better bike lanes, this is what can happen.

“If you design better public spaces, you change the relationship residents have with a city, and also with each other.”

— Matúš Vallo

A metropolis where children start walking to school, or locals meet at new outdoor cafés, is one whose fabric changes in untold ways.

Most politicians think residents shape the built environment to suit their lifestyle.

It takes an architect to think that it is the built environment that shapes its residents.

Bratislava is the capital of Slovokia, a city of about 500,000 or 600,000 residents on the Danube River, along the border with Austria. There have been human settlements there since the Stone Age, and it has existed as a city with streets for over a thousand years. The city of Vienna is abut an hour and fifteen minutes away, driving or via a $12 train ticket.

Slovakia was peacefully split from from the made-up country of Czechoslovakia in 1993, thirty years ago. To learn more of the history of modern Slovakia, see below.

Matúš Vallo was elected mayor first in 2018 and then re-elected in 2022 with over 60% of the vote. He is currently 46 years old. Professionally he is an architect. Prior to his election, he was known as an urban activist and the bass player of a popular rock band.

Contents

- Meet Matúš Vallo, Bratislava’s hipster mayor-architect

from The Economist September 16, 2023 issue - Bratislava’s the Old City is car-free – Pictures

- Bratislava removes two car lanes on the road along the Danube, and replaces the space with bike lanes – Pictures

- A brief history of modern Slovakia

Meet Matúš Vallo, Bratislava’s hipster mayor-architect

Can better public spaces revolutionize the way we live?

from The Economist September 16, 2023 issue

In the manner of a child rebuilding an unloved Lego set, Matus Vallo ponders a model of a Bratislava streetscape in a corner of his office. Carefully, he positions a rectangular plate the width of his palm on a section of highway that has run through the capital of Slovakia since the 1970s. Just like that, a park over 200 metres long, suspended above the road, has eradicated a traffic-laden scar in the heart of the city. The transformation seems fanciful, an urban planner’s daydream. To turn it into reality would require the combined talents of an architect, a civic activist and a popular mayor. By some fluke Mr Vallo happens to be all three — and the answer to the question: What happens when an expert in building public spaces gets given the reins of a European capital?

To run a city requires a plethora of political talents, from baby-kissing to haggling with central government for more funding. Mr Vallo brings different skills to the job. In 2018, as an architect with a thriving practice, the self-described “urban activist” rode a wave of political discontent into office (he had previously been more famous as the bass player for a popular rock band). His pitch to the citizens of Bratislava focused on the need to improve the look and feel of the place. “If you design better public spaces, you change the relationship residents have with a city, but also with each other,” he explains. A metropolis where children start walking to school, or locals meet at new outdoor cafés, is one whose fabric changes in untold ways. Mere politicians think residents shape the built environment to suit their lifestyle. It takes an architect to think it is the built environment that shapes its residents.

With his trendy beard, sneakers tied with fluorescent shoelaces and fold-up Brompton bike, the 45-year-old exudes metropolitan hipster idealism. The city needs it. Though blessed with a delightfully pretty Old Town at its centre — including a neoclassical mayoral palace where Mr Vallo works — Bratislava endured decades of communist architectural drabification. After 1989 [when democracy was restored], property developers did their best to make capitalism look even worse; uninspiring office towers went up alongside uniform shopping malls. Indifferent management by mayors using the town hall as one more step on their career paths hardly helped. In time the city was not only missing the cycle lanes and pleasant outdoor spaces found in other European capitals: it had no soul, no sense of itself.

One design decision at a time, that is being rectified. Some schemes championed by Mr Vallo are hard to miss. The city’s Freedom Square had long been dominated by a forbiddingly monumental fountain, better to take up space the communist authorities feared might one day be filled by protesters. A clever redesign inaugurated this summer turned the fountain into an inviting aquatic playground where kids can splash around.

Part of the city’s embankment is being turned over to cyclists. Parking charges [i.e. metered parking] have become the norm, annoying car users but giving more public space to wheelchairs and prams (perhaps not coincidentally, Mr Vallo became a dad while in office). A crusade against “visual smog” has resulted in hundreds of garish billboards being cleared.

But the mayor reserves his capacity for excitement — no politician bar Donald Trump uses the word “fantastic” quite so freely — for subtler improvements to his city. As streets get rebuilt, grey asphalt is being replaced by light-hued paving stones featuring patterns commissioned by the town hall. Few guests to Mr Vallo’s office have been spared mayoral tirades extolling this design, your columnist included. There is new street-lighting and hundreds of stylish park benches worthy of further mayoral gushing. In most cities decisions on how such things should look are taken haphazardly. In Bratislava these days a coherent vision is applied from the top. A slew of architectural manuals lying on the mayor’s desk explain to city staff what traffic islands should look like from now on, or the apparently Platonic ideal of a Bratislava flower bed. Street by street, a theme is emerging.

Mr Vallo has done two clever things. The first was to prepare for the job. For two years before he won office, he led a “collective” of around 70 like-minded creative types to devise “Plan Bratislava”, a sort of blueprint for fixing its problems, now being enacted.

The second was simply to pinch [steal] what the world’s well-run cities have already done. Some of Mr Vallo’s best ideas are proudly filched: the cycling embankment from Paris, those stylish benches were first seen in Prague, and so on. “You don’t need to experiment if other cities have made the mistakes for you,” he says.

Mr Vallo’s stints living in Rome (as the son of a diplomat), London (for work) and New York (a Fulbright scholarship at Columbia) no doubt helped. In New York he fell under the spell of Mike Bloomberg, the three-term mayor. Now Bratislava is tapping the billionaire’s philanthropic arm for advice on how world-class cities are administered.

Mr Vallo is palpably frustrated at the pace of change. Cycle lanes take ages to build; the road-replacing park he toys with in his office remains elusive—though Mr Vallo insists it will happen. Covid slowed down many schemes. No matter: he was re-elected with over 60% of the vote last year. That may prove a political high point. Robert Fico, a Kremlin-loving populist who was swept out as prime minister by the same wave that brought in Mr Vallo five years ago, is leading the polls ahead of national elections on September 30th. That might leave Mr Vallo as an isolated liberal mayor in a country drifting to extremes. Such is the lot of many of his peers these days in illiberal central Europe: the mayors of Bratislava, Budapest, Prague and Warsaw have even formed a “pact of free cities”. The quartet travelled together to Kyiv in January.

It would take decades of relentless Vallo-ism for Bratislava to turn into Vienna, its stunning neighbour just 55km [35 miles] away. Fans of the city swear it is like Berlin a generation ago, the up-and-coming city then undiscovered by the masses. There is much to do to get there, and nearly as much enthusiasm to keep at it.

Bratislava’s the Old City is car-free

In Bratislava, the Old City is car-free, for walking only.

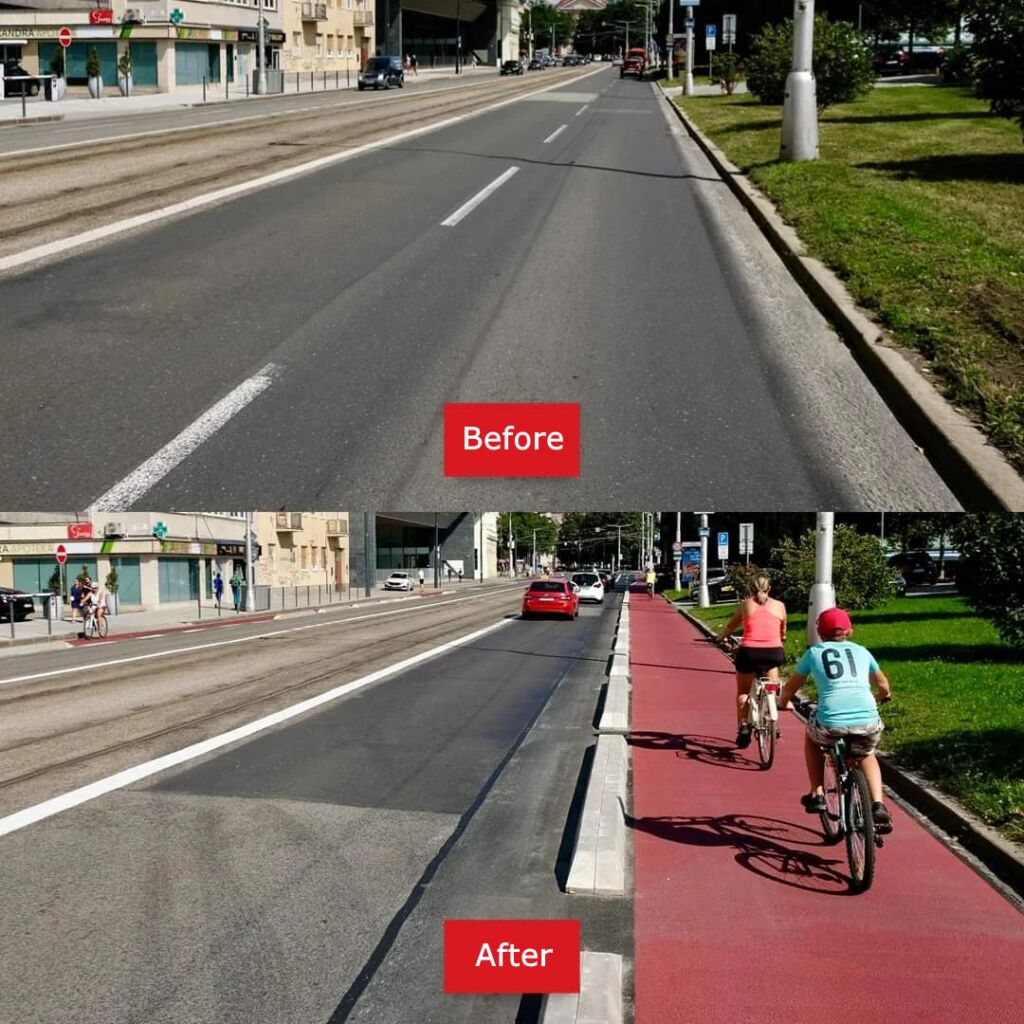

Bratislava removes two car lanes on the road along the Danube, and replaces the space with bike lanes

A city street that had two car lanes in each direction now has one car lane and one bike lane. The “empty” area in the center of the street is for the trolleys.

A brief history of modern Slovakia

Czechoslovakia was formed from several provinces of the collapsing empire of Austria-Hungary in 1918, at the end of World War I. Between the end of WWI (1918) and the start in Europe of WWII (1939, just 21 years), it became the most prosperous and politically stable country in eastern Europe.

After World War II, in 1948, Czechoslovakia, until then the last democracy in Eastern Europe, became a Communist country, starting more than 40 years of totalitarian rule. It’s leader at the time feared a Soviet invasion and civil war.

Twenty years later, in 1968, a popular movement to restore true democracy in Czechoslovakia gained momentum. At first, the Soviet Union intervened politically to appoint their chosen leaders of the government, but the Czechoslovak people were entirely against the Soviet Union directing their country. Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia on August 20, 1968, with a full military invasion, including tanks and troops in the streets of Prague.

About twenty-one years following the Soviet invasion, the Velvet Revolution, a nationwide protest movement in Czechoslovakia, ended more than 40 years of communist rule in the country. A wave of protests against communist rule erupted in eastern Europe. Daily mass gatherings culminated in a general strike in November 1989, during which the people demanded free elections and an end to one-party rule.

Václav Havel, a dissident playwright, was elected to the post of interim president of Czechoslovakia on December 29, 1989, and he was re-elected to the presidency in July 1990, becoming the country’s first non-communist leader since 1948.

In 1992, a peaceful agreement was reached among the country’s leaders to dissolve Czechoslovakia. On January 1, 1993, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic each simultaneously and peacefully proclaimed their existence.