[player id=’3011′]

For more articles on Form-Based Code on this website, click here.

Ben Noble: Form-Based Code presentation

June 29, 2022

Ben Noble is the City/Planwest independent consultant who is developing the Gateway Form-Based Code. This presentation is about 1 hour long, followed by ~20 minutes of viewers’ questions and answers.

This is a “must-read” article for everyone interested and involved in the Gateway plan.

The video can be seen on the Arcata’s YouTube channel. In the original version the audio of Ben speaking was very muffled. In listening to that video now, it seems audio has been cleared up somewhat, but it’s still not too clear. The audio does not sync with the video — when people are talking, what you see doesn’t match what you hear — but for most of the presentation that isn’t a problem.

The audio track here has been enhanced for clarity. All the diagrams, drawing, photos, and examples from the original Zoom recording are included here.

- A great resource on Form-Based Code: Ben’s presentation is clear, complete, and for the most part easy to understand. There is a lot of information here, and he presents it well. Thank you, Ben!

- Ministerial review: From the beginning, Community Development Director David Loya has been making a case for what he referred to as Ministerial Review. That is, as he spoke of it: Projects would be reviewed by one person, the Zoning Administrator (i.e. David Loya) and there would be no public input. The Planning Commission, as might be expected, was in favor of what was termed “Discretionary Review” — a process of public input and Planning Commission review. There are articles on this website that speak to this difference of viewpoint.

The problem, evidently, is that none of us were using the phrases “ministerial review” and “discretionary review” correctly — not David Loya, not the Planning Commission members, and not myself. In this presentation, Ben Noble establishes three options for ministerial review. And “Option Three” does include public input and Planning Commission review.

- There are BIG aspects of this presentation that I have issues with. This are covered in other articles on the Arcata1.com website here. Ben seems to be skilled and talented — and he MUST be given the right input so he can write a Form-Based Code that expresses the will of the community. Some of the Form-Based Code in the other communities he provides as examples are just terrible (in my view) — such as the Meriam Park development in Chico. People may disagree with this statement: A code that makes it easy for developers is generally not so beneficial to the community.

To quote a friend, a Grammy-winning musician who regularly travels around the country and around the world: “Have you ever noticed that in the places where they make it good for the developers, it’s usually not so good for people?”

- As mentioned, the audio in the original video is quite bad. Perhaps Ben’s microphone is broken — his voice is muted and indistinct. In the audio here, efforts were made to increase the clarity. This introduced some other distortions, but overall results in a voice quality that is far better than the original, though still not as good as a good recording should be. Best would be for Ben to re-record the entire hour of his presentation, according the transcript here.

Opinion: This presentation should have been scheduled and the information made available to the Planning Commission, the City Council, and the public three or four months ago, at a more appropriate point in the ongoing Gateway process. That would have given us ideas and answered endless questions, and have moved us much further along in the creation of a good plan for Arcata. But no sense in crying of the spilt milk of the past, right? Except that it’s yet another example of how our own City Staff has hampered and stymied and, in my view, harmed this Gateway process.

And I would have thought that Community Development Director David Loya would have brought up “Option Three” of the ministerial review, which includes public input and Planning Commission review. But he did not. Possibly because he did not want to remove the confusion at the Planning Commission level and with the public, or possibly because he did not know himself.

This transcription is believed to be an accurate rendition of what was said. Any discrepancies between what was spoken and what is written here are unintentional and are not believed to alter the intent or meaning of the speaker. Many of the “uh” and “you know” and “um” and “And so” words have been removed. Some sub-headings have been added.

If you see errors in the transcription, please write — using the Contact Us page or to Fred at this website: Arcata1.com.

Your help in making this website better is appreciated.

The transcript is in black text. Highlights have been added as bold highlights. Notes have been added in Green and comments have been added in Red. The comments and opinions are those of the author and are not presented as fact, but as opinion.

How to listen to the audio

Click the Play button ![]() to start the audio. That button becomes the Pause button

to start the audio. That button becomes the Pause button![]() while playing.

while playing.

The audio player will “float” at the top of the screen, so you can access it at any time. You can pause or go to a specific time-spot in the audio. The time of where you are on the audio track is visible when you hover the mouse over the timeline. On the small screen of a cell phone, it’s not so easy to move around on the audio timeline, sorry.

The audio/video times are included in the text, so you can easily jump to that section of the audio. The times shown are approximate, not exact. The entire audio is 1 hour, 34 minutes.

David Loya 00:05

Welcome. Thanks again for joining us today. We’re pleased to be kicking off sort of the design phase of the Gateway area plan, and starting to do some outreach and engagement on what this area could look like in the future. And so we’re happy to have all of you join us today.

My name is David Loya, I’m the Director of Community Development of the City of Arcata. I’m here with my colleague Delo Freitas, Senior Planner, and Ben Noble, who’s part of our consultant team that’s helping to pull together this work, as well as some of the General Plan updates that we’re working on. And so we’re pleased to have him with us today. He’s going to walk us through what Form-Based Codes are, how they can be applied in Arcata, and what the permitting pathways could look like.

And so we’re excited to be doing this phase.

Today’s presentation is primarily to try and get information out about Form-Based Codes and to try and answer your questions. There will be follow-up in subsequent phases where we’ll be doing more community design engagement and having more of a discussion around what should be incorporated into a Form-Based Code that could be adopted for the City of Arcata. So it’s a multi-step process, you’re not going to get it all in this first meeting, although I know, we’re all very anxious to see the results of this — it will take time for us to roll all of this engagement out and make sure that we’ve got full participation.

So I’m excited to kick this off. And the one thing I’ll say before I turn it over to Ben is that part of the reason we’re doing this on Zoom is so that we can have a recording of the meeting. The meeting is being recorded. And we’ll be able to use this in a couple of different ways to reach out and engage with folks that weren’t able to take the time out of their day today to attend this lunchtime meeting. I realize it’s a quick turnaround on meeting time and also kind of an odd time to have a meeting. But the purpose is to be able to use this recording as a way to use this engagement with other people. So to that end, if you have a group that you’d like us to do a “we’ll come to you” session with, we can bring this recording and do basically this exact same meeting with that group. So with that I’d like to turn it over to Ben. And we have others on our City team and consultant team that we can bring in as needed. So thank you, Ben. Take it away.

Ben Noble 02:51

Thanks, David. And welcome, everybody. It’s great to see the number of participants that we have. I’m going to share my screen and then endeavor to get a presentation. So can everybody see where, David, we’re dealing with the title slide. Great. Looking great. Excellent.

So as David mentioned, my name is Ben Noble. I’m part of the consultant team working on the Gateway area plan. I’m inside sub-consultant to Planwest Partners on this work. And I’m based in the San Francisco Bay area and really delighted to be working with David, Delo and other members of Arcata city staff on this important project.

My background is: I’m an independent consultant sole-proprietor focusing on development code updates, including Form-Based Codes. I’ve been doing that independently for about eight years. And prior to that I was a principal at a larger firm, Placeworks, where I oversaw the zoning practice.

And as David mentioned, as part of the Gateway area plan, there’s the intention to prepare a Form-Based Code that will regulate development in this area. And so, as an initial meeting today, we want to provide some background information and an introduction to Form-Based Codes to help inform the process as we move forward.

And as David mentioned, as part of the Gateway area plan, there’s the intention to prepare a Form-Based Code that will regulate development in this area. And so, as an initial meeting today, we want to provide some background information and an introduction to Form-Based Codes to help inform the process as we move forward.

This presentation will be divided into three parts. The first part will be an introduction to Form-Based Code generally. The second part will be to speak more specifically that the plans for the Gateway area Form-Based Code. And then the third part will focus on a particularly important aspect of the code, which is the permits and approval requirements.

So Part One, I’m going to cove r what a Form-Based Code is, and provide examples of Form-Based Code from other communities.

r what a Form-Based Code is, and provide examples of Form-Based Code from other communities.

Here’s a working definition of what a Form-Based Code is. Essentially, it’s a land development regulation that implements a plan with physical form as its organizing principle.

So a Form-Based Code emphasizes the relationships between building facades and the public realm, form and mass of buildings in relation to one another, and the scale and types of streets and open spaces. Form-Based Code de-emphasizes the separation of uses. And the code contains objective standards, not guidelines or subjective requirements. And lastly, a Form-Based Code presents the standards in both words, clearly drawn diagrams, and other visuals.

So I understand there’s a lot to unpack on the slide, but I’m going to go through it in a little bit more detail, particularly by providing examples.

One way to think about this is to compare a Form-Based Code to more traditional zoning, similar to what you may be familiar with, with the city’s land use code. So while traditional zoning is generally more text-focused, in a Form-Based Code standards and requirements are presented in a more graphical-focus way. Whereas traditional zoning focuses on allowed land uses and land uses that are not allowed, a Form-Based Code is primarily focused on physical form. Whereas traditional zoning often relies on subjective requirements, say, for example, through design-review criteria  or findings, Form-Based Codes are focused more and based on objective standards. The traditional zoning code often is focused on land-use segregation and separation of uses within zoning districts, whereas a Form-Based Code is more oriented towards mixed-use. And then traditional zoning is typically focused on what can happen on one individual property, whether that’s allowed land use or development standards, whereas a Form-Based Code is taking a more holistic look at neighborhoods and districts, and focusing on how development relates to other development as well as to the public realm as well. And then lastly, traditional zoning tends to be more prescriptive in terms of identifying what you can’t do. Say for example, a setback: A building cannot be located closer than 15 feet from the property line, for example. Whereas a Form-Based Code tends to be more proscriptive, where it’s identifying what is desired or required. And an example of that might be a build design, where development is required to be located at a certain distance from the property line or within a zone adjacent to the property line. So this table is another way to help think about the differences between more traditional zoning codes.

or findings, Form-Based Codes are focused more and based on objective standards. The traditional zoning code often is focused on land-use segregation and separation of uses within zoning districts, whereas a Form-Based Code is more oriented towards mixed-use. And then traditional zoning is typically focused on what can happen on one individual property, whether that’s allowed land use or development standards, whereas a Form-Based Code is taking a more holistic look at neighborhoods and districts, and focusing on how development relates to other development as well as to the public realm as well. And then lastly, traditional zoning tends to be more prescriptive in terms of identifying what you can’t do. Say for example, a setback: A building cannot be located closer than 15 feet from the property line, for example. Whereas a Form-Based Code tends to be more proscriptive, where it’s identifying what is desired or required. And an example of that might be a build design, where development is required to be located at a certain distance from the property line or within a zone adjacent to the property line. So this table is another way to help think about the differences between more traditional zoning codes.

Another very important aspect of a Form-Based Code is its reliance on objective standards, as I mentioned. And State law has a definition of objective standards that appears in various locations within the government code and it’s on the screen here. An objective standard involves no personal or subjective judgment by a public official and these standards are uniformly verifiable by reference to an external and uniform benchmark or criteria. And this is available and knowable by both the development applicant or proponent and the public official prior to submittal.

Another very important aspect of a Form-Based Code is its reliance on objective standards, as I mentioned. And State law has a definition of objective standards that appears in various locations within the government code and it’s on the screen here. An objective standard involves no personal or subjective judgment by a public official and these standards are uniformly verifiable by reference to an external and uniform benchmark or criteria. And this is available and knowable by both the development applicant or proponent and the public official prior to submittal.

This is the objective standard definition that appears in State law, and, as the City proceeds with the Form-Based Code for the Gateway area, ensuring that we establish objective standards for the Code is going to be particularly important. So here’s an example comparing a subjective requirement to an objective standard. So a subjective requirement might be something like, provide for active storefronts that support pedestrian activities. You might find this kind of requirement in a design review finding, for example. An objective standard that addresses the same issue might be something like blank walls or more within 10 linear feet are prohibited along any street basic facade. And this is a very simplified standard, I understand. But it is an example of an objective standard where there’s no personal or subjective judgment involved. It’s something that can be verifiable and knowable in advance by an applicant, city staff and the public as well.

This is the objective standard definition that appears in State law, and, as the City proceeds with the Form-Based Code for the Gateway area, ensuring that we establish objective standards for the Code is going to be particularly important. So here’s an example comparing a subjective requirement to an objective standard. So a subjective requirement might be something like, provide for active storefronts that support pedestrian activities. You might find this kind of requirement in a design review finding, for example. An objective standard that addresses the same issue might be something like blank walls or more within 10 linear feet are prohibited along any street basic facade. And this is a very simplified standard, I understand. But it is an example of an objective standard where there’s no personal or subjective judgment involved. It’s something that can be verifiable and knowable in advance by an applicant, city staff and the public as well.

10:25

Okay, so now I’m going to get into a little bit more about what the Form-Based Code is and dive into a little bit of history of recent history of zoning, urban design, and planning. What I have on the screen here is something of an iconic image in the world of city planning and urban design. It’s an image of what’s known as the Urban-to-Rural Transect.

This is a concept that came out in the late 1990s by a group of architects and designers known as New Urbanists. This group aimed to promote environmentally sustainable development with more walkable neighborhoods, with a wide range of housing and a mix of land uses. And one of the champions among the New Urbanists was an architect by the name of Andrés Duany.

[For more information on the New Urbanist movement and Andrés Duany, a good start are these Wikipedia links: New_Urbanism — Andrés Duany]

When Duany analyzed the state of cities in urban form in the United States at that time he identified traditional zoning as a source of many of the problems facing urban communities in America in terms of the separation of uses, of the focus on allowed land uses rather than urban form, and ignoring aspects of the public realm and placemaking objectives. So Duany thought that we needed a different way of thinking about land development regulation, and that instead of a use-focus zone as an organizing principle, he proposed the Urban-to-Rural Transect. And this concept envisions the built environment as a continuum of place types that transitions from the least intensive to the most intensive. And each of these place types are Transect Zones, defined primarily by urban form rather than allowed values. And this Urban-to-Rural Transect provided a foundation for a new type of zoning code, referred to as a Form-Based Code. Duany and his firm Duany Plater-Zyberk [with his wife, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk] were one of the early champions of Form-Based Codes. His Form-Based Code is something that is referred to as a Smart Code. And so you’ll see Smart Codes around today. They typically will establish transect zones with the numbers T1, T2, and T3. And where that comes from, is the transect concept illustrated by this diagram.

13:30

13:30

And then so moving forward today, it’s been about 25 years since the first Smart Code came out, and Form-Based Codes have evolved. But many of the underlying line principles remain the same. And this transect concept is one of them, with modern Form-Based Codes organized around a series of space-based districts that range from the least to the most intense. So on the screen I’m showing a graphic that’s illustrating zoning districts for the recently adopted South Bend, Indiana, Form-Based Code, which is an excellent code that’s helping to revitalize a mid-sized Rust Belt community in the Midwest. And so I’m going to show a number of examples from this code because I think it does a really good job of graphically illustrating what a Form-Based Code is all about. And I think this graphic is interesting, because you can see on the top, sort of this less urban to more urban continuum that’s reflective of the transect concept that Duany put forward 25 years ago.

14:40

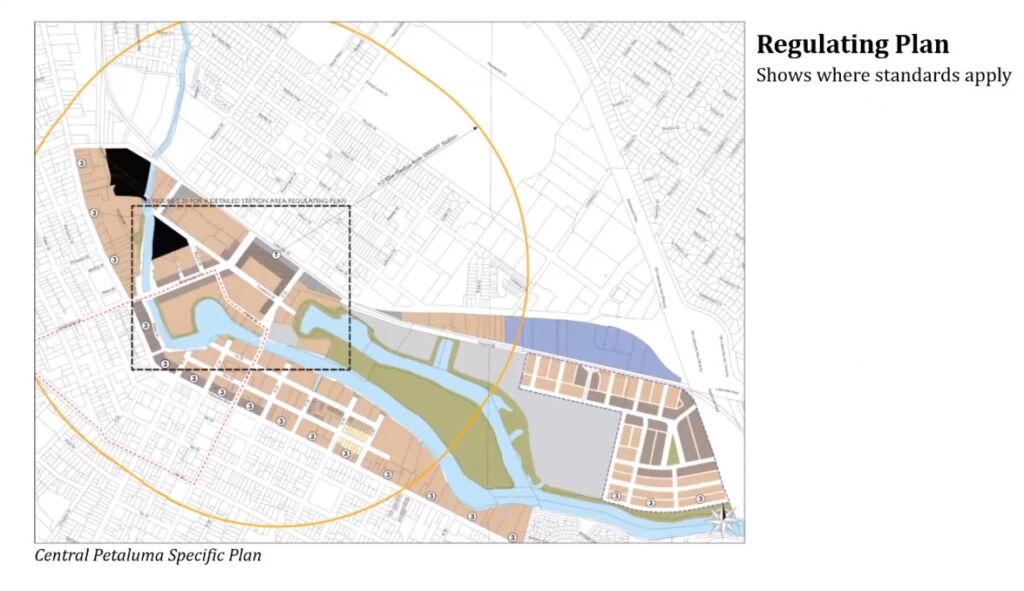

Most but not all Form-Based Codes are applied to a specific geographic areas. And so, as such, the code needs a map or a diagram that shows where different rules apply. And the mechanism that a Form-Based Code uses for this is what is typically referred to as a Regulating Plan, which may look similar to a zoning map, but it’s different from a zoning map in a number of different ways. And what I have on the screen is the Regulating Plan, I should say, part of the Regulating Plan from the Central Petaluma Specific Plan, which was one of the early Form-Based Codes in California. And one of the things that’s different with a Regulating Plan compared to a zoning map is that it’s not just about districts and allowed uses but it’s also about the public realm. So a Regulating Plan may include location-specific standards for open space, for streets, how buildings relate to the public realm, sometimes standards as illustrated in the Regulating Plan are block-specific with different rules for specific properties even within the same transect or zoning or Form-Based Code district. And so this is an important foundation for any Form-Based Code.

Most but not all Form-Based Codes are applied to a specific geographic areas. And so, as such, the code needs a map or a diagram that shows where different rules apply. And the mechanism that a Form-Based Code uses for this is what is typically referred to as a Regulating Plan, which may look similar to a zoning map, but it’s different from a zoning map in a number of different ways. And what I have on the screen is the Regulating Plan, I should say, part of the Regulating Plan from the Central Petaluma Specific Plan, which was one of the early Form-Based Codes in California. And one of the things that’s different with a Regulating Plan compared to a zoning map is that it’s not just about districts and allowed uses but it’s also about the public realm. So a Regulating Plan may include location-specific standards for open space, for streets, how buildings relate to the public realm, sometimes standards as illustrated in the Regulating Plan are block-specific with different rules for specific properties even within the same transect or zoning or Form-Based Code district. And so this is an important foundation for any Form-Based Code.

16:20

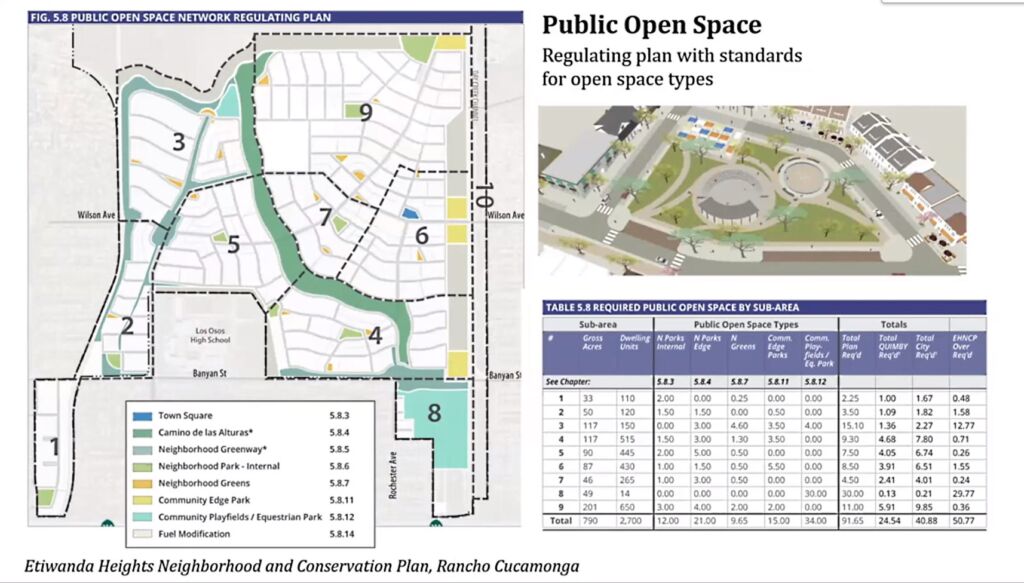

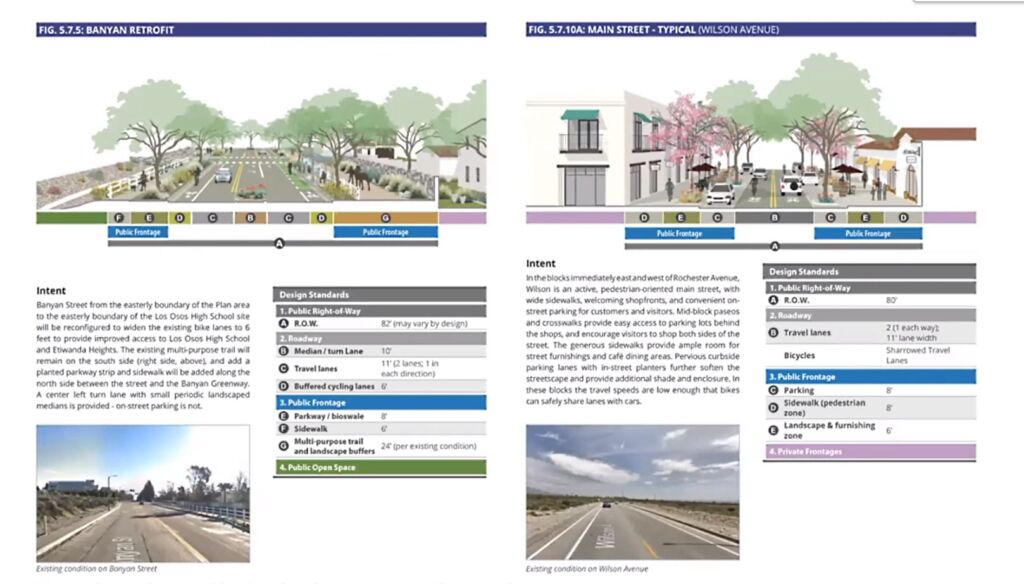

And a Form-Based Code often applies within an existing urban area. But it can also be used for greenfield development, as well as urban infill, and to create new neighborhoods where development previously didn’t exist. So here’s an example of a Form-Based Code with that kind of a setting. It’s for a plan and a code down in Southern California in Rancho Cucamonga. And this is a code for a new neighborhood on the edge of the city. In addition to establishing districts through the Regulating Plan, it also establishes the layouts of streets and open spaces and how those are connected in an effort to create a complete neighborhood.

[Note: Greenfield describes new development on undisturbed land i.e empty former industrial parcel or ag land, while Brownfield refers to the infill or re-development in an area of existing buildings. In the Gateway plan here in Arcata, the area along Samoa Boulevard where the logs are and the lumber mill is would be considered Greenfield — there would be roads made where there were no roads, there would be new parks, new paths, and so forth. All other development in the Gateway area involves fitting new buildings alongside current buildings, on existing streets, in established neighborhoods.]

17:20

Okay, so now going back to the transect concept, here’s a series of illustrations that show the forming characters of districts along a continuum, from the least intensive to the most intensive. These diagrams, again, are from the South Bend zoning ordinance. And on the screen now is an illustration for the “Urban Neighborhood 1” district. And you can see characteristics of this district in terms of building width, building depths, heights, frontages of the homes, the streetscape design, as well as the roadway design.

18:00

And here’s an illustration moving to a more intensive residential neighborhood where you can see different building types, different treatments for planning improvements, and different site layouts with unique building typologies.

And, again, here is the illustration for a neighborhood serving commercial district with a very different urban form both for the mixed-use development as well as for the residential-only development off of the main street, really thinking about how building form and standards for the public realm support placemaking and creating complete neighborhoods.

And, again, here is the illustration for a neighborhood serving commercial district with a very different urban form both for the mixed-use development as well as for the residential-only development off of the main street, really thinking about how building form and standards for the public realm support placemaking and creating complete neighborhoods.

And then lastly, here’s the most intensive district in this code for the downtown setting.

And then lastly, here’s the most intensive district in this code for the downtown setting.

[Note: The tallest building shown is 8 stories, with surrounding buildings of 3-4-5 stories. This car-centric depiction of downtown South Bend, Indiana, is a somewhat typical American urban downtown scene.]

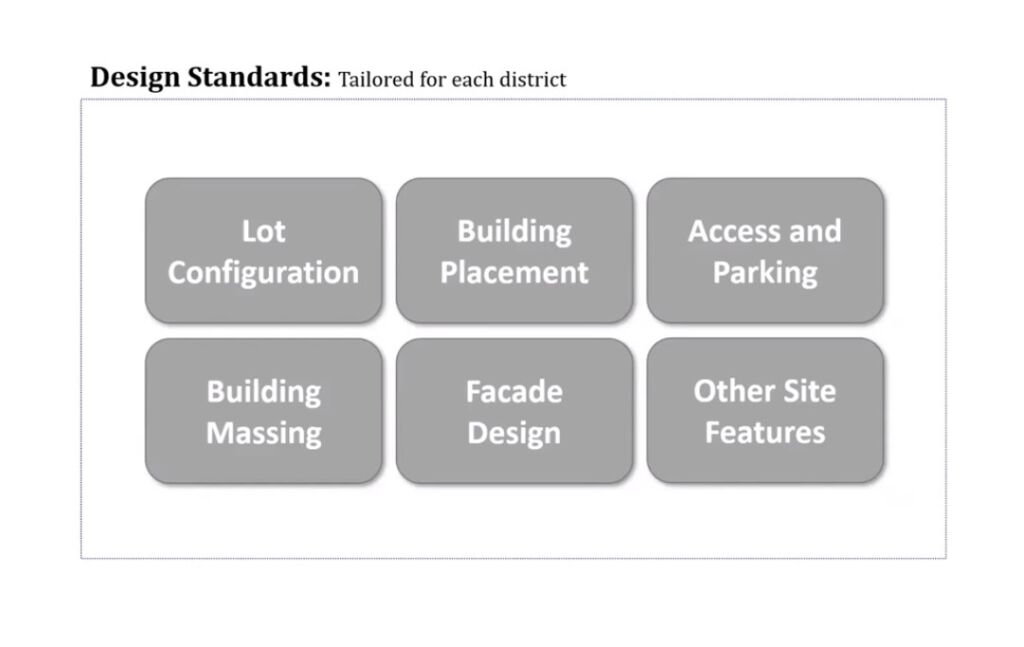

So for these different districts that are based primarily on form and character of Form-Based Code will establish objective standards as a central organizing principle. And I like to think about these standards as being organized around six dimensions of proscriptive standards. The standards typically focus on how buildings relate to one another and public spaces as well as the public realm. So it starts with lot configuration and building placement, access and parking, building massing, facade designs, and other site features. So a Form-Based Code will address all of these different aspects of urban design designed tailored for each individual district.

19:50

19:50

I’m going to show some images of how a Form-Based Code might address these different dimensions of urban design. Here’s a diagram again from South Bend [Indiana] that is showing standards for lot configuration and building placement. As I mentioned previously, Form-Based Codes are often very graphic in terms of the way that they present standards. And this is a good example of that. So on the left, you have a diagram that’s accompanied by a table on the right, and these two work together. And a couple of things I think are notable about these lot configurations of building placement standards is that with setbacks, there’s both a minimum and a maximum setback. There’s a requirement for a certain percentage of the street-facing building facade could be located within a setback zone. And the standards are proscriptive, rather than prescriptive.

The Form-Based Codes are often very concerned about the placement and design of parking and access to that parking because of the impact that parking and vehicle access can play on the quality of the pedestrian environment. So here’s an example of standards which require parking to be located on a certain area of the property behind a street-facing building and establishing rules for where vehicles can access that parking. Essentially, if a property is served by an alley and it’s an interior lot, the parking access must be provided from that alley. So that type of standard is also common in the Form-Based Code.

21:50

21:50

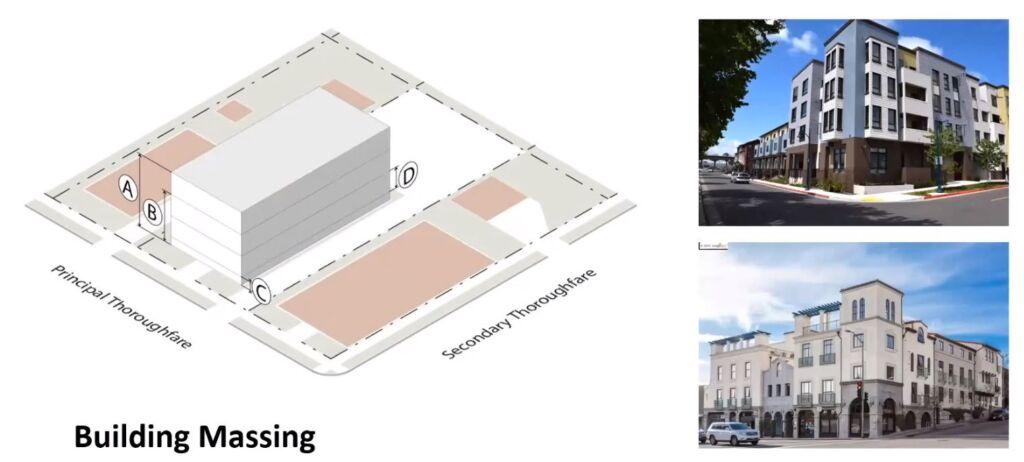

Okay, so building massing. This is a simple diagram that’s illustrating minimum and maximum heights, as well as required upper story setbacks. Form-Based Codes often are very interested in objective standards for building massing — requiring variation, building heights, establishing maximum building widths, and requiring for reduced intensity, reduce heights, for example, when adjacent to lower intensity residential uses.

And then here is facade design. So it’s the design of the skin of the building. This standard is illustrating a minimum transparency requirement that applies to both the ground floor and the upper floor. There’s facade articulation standards here as well as corner building treatments.

[Note: “Building articulation refers to the many street frontage design elements, both horizontal and vertical, that help create a streetscape of interest. The appropriate scale for articulation is often a function of the size of the building and the adjacent public spaces including sidewalks, planting zones, and roadways.” “Articulation techniques promote a more human scale throughout building design by dividing building mass into smaller parts.” “Articulation refers to the fragmentation of form and surface in order to break large uninteresting or oppressive mass into more human size components. People respond better to articulation for it relates to them in scale and they feel more comfortable when they can move amongst elements rather than be exposed against a backdrop of singular planar surfaces.”]

22:58

22:58

And then lastly, a Form-Based Code will often include standards for other site features, whether it’s mechanical equipment, trash and recycling containers, fences and walls, and other things like that, that are important to achieve quality design.

Many of those standards may be familiar to you to you, if you’re familiar with more conventional traditional zoning codes. But one thing that is very unique about Form-Based Codes in a way that it departs from traditional zoning is with standards for building types. On the screen, these are some illustrations of building type standards from the Buffalo Green Code recently adopted in New York State. I am showing two examples of building types. On the left is a townhouse, and on the right is a stacked flats. And this sort of this focus on building typologies, I think, reflects a lot of the thinking of the New Urbanists and their work on Smart Codes. And thinking about — in different place types, in different types of neighborhoods, different transect zones — there are certain building typologies traditionally that defined those places and then in a lot of ways they have been lost in cities in America, as development and housing development has become more standardized. And there’s a desire to bring back into community some of these more traditional building forms that support a pedestrian oriented environment. There’s also a desire to encourage a range of housing types, not just apartments or single-family homes, but lots of different configurations for multi-unit housing, to provide for greater choice and diversity of available housing. And so in a Form-Based Code, the codes will often identify specific building types. The codes may identify different areas where these types are permitted. And then we’ll establish standards that apply, that are unique to these individual building types that might apply in addition to district-based standards.

25:33

Another thing that is emphasized within Form-Based Codes, is something that’s often referred to as frontage types.

And this comes from a focus on how buildings relate to the public realm in a way that supports a pedestrian-oriented environment. I’m really thinking about the relationship between building facades and public realms. So what Form-Based Codes often do they identify different frontages with what is referred to as a terrace.

And this comes from a focus on how buildings relate to the public realm in a way that supports a pedestrian-oriented environment. I’m really thinking about the relationship between building facades and public realms. So what Form-Based Codes often do they identify different frontages with what is referred to as a terrace.

26:10

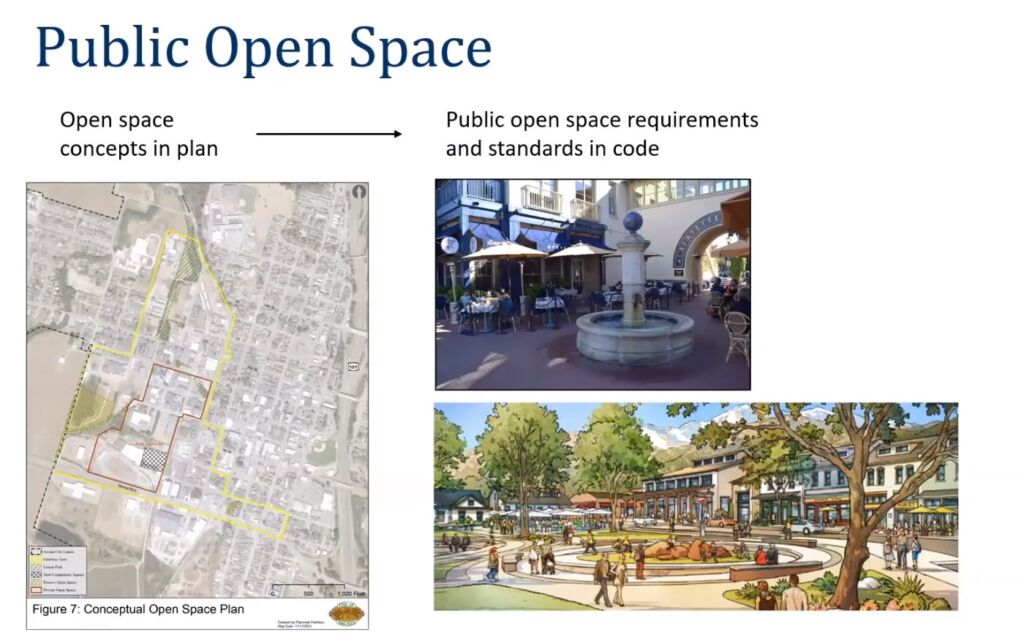

Another thing that’s interesting about Form-Based Codes that when it applies to areas where new streets are particularly traditional. So a Form-Based Code, being very focused on the design of the public realm will often contain standards for open spaces. So the code may include a regulating plan that identifies the location and the types of publicly accessible open space with standards for these different types of spaces.

26:40

So that’s sort of an overview of what a Form-Based Code is, what it’s trying to accomplish in some of the typical contests. I’m going to now transition into the second part of this presentation where I’m going to be providing some examples of Form-Based Codes in Northern California. And I’m really looking here at smaller cities that are outside of major metropolitan regions, codes that have been around a while, where we’ve seen some development. Understanding that these are older codes and the state of the art on Form-Based Codes has evolved. But I think they’re still interesting and instructive to go into.

[Why show us older codes? Are there not better examples of more recent codes for us to look at?]

Form-Based Code Example: Central Petaluma Smart Code

Back to the Central Petaluma Specific Plan. Many of you probably know Petaluma is a city in the San Francisco Bay area. It’s about 40 miles north of San Francisco, in Sonoma County. And historically it’s been a center of agriculture and agricultural-related distribution and manufacturing. So within Petaluma in the central area of the city there’s a large area of underutilized land. And the city about 20 years ago adopted a plan that aims to reinvigorate the central district. And as part of this plan they adopted a Smart code Based on Transect Zone Concept. And here’s some photographs of development that have occurred in Petaluma over the last 15 years. Most new development has occurred south of the river in an area known as the Theater District. Most development has been in the form of mixed-use residential, with housing above ground-floor commercial. One of the things in the code as a Smart Code is that there’s emphasis on frontage types. And the code identifies certain locations where shop-front terrace, in our case, frontage types are permitted.

Here’s an example of a shop-frontage type with standards for these different types of private frontages. There are rules related to ground-floor transparency, the maximum depth of recess entries in awning dimensions and, from my perspective, this building does a pretty good job of achieving a pedestrian-friendly, friendly ground-floor presence that’s active and that’s inviting. Part of the reason that it accomplished that is through the standards — for shop-front frontage types within the Form-Based Code.

An important part of the Petaluma Smart Code is standards for civic spaces. The code identifies permitted types of civic spaces — such as parks, squares, greenways plazas, pocket plazas — and identifies the permitted location of these different types. For one sub-area in the plan, there’s actually a Regulating Plan of a specific space that identifies the location of required civic spaces and the type and standards that apply to them. So I think what we’re looking at here is probably a pocket plaza included as part of new development. And within the code their standards for both the minimum and the maximum size of this plaza. And I think most importantly standards for adjacent building furniture. I think one of the reasons why this publicly-accessible open space is successful is because you have storefronts that are immediately adjacent to and open out into this public space, activated to create sort of a welcoming environment for people

30:45

So the Petaluma code also regulates by building types. It identifies a range of permitted building types and the location. I think what we’re seeing here is an example of a “Main Street” building type. And this is something that reflects the historic development in Central and Downtown Petaluma. In their standards that are attached to this building type, there’s a minimum and maximum building height. There’s a maximum width and depth to the main body of the building. There’s allowed frontage types, there are rules for parking, access and placement, as well as access to upper-level residents. I think most people visiting Central Petaluma would find this development to be successful, or at least successfully implemented the vision of the Central Specific Plan. And part of the reason for that are the proscriptive standards in the Form-Based Code for this building type.

Form-Based Code Example: Meriam Park – Chico, California

31:49

Okay, now I’m going to move on to something that is kind of completely different and a different kind of application of the Form-Based Code concept. In Chico — Chico, within their zoning code has a Traditional Neighborhood Development, or TND Zoning District. Many of you may be familiar with the TND concept. This is something, again, that came out of the New Urbanists in the 1990s, Andrés Duany was a champion.

The TND concept aims to achieve a complete walkable neighborhood, defined by a neighborhood center with a mix of uses, a mix of housing types, an interconnected street network, a pedestrian-friendly streetscape, and public open space. So based on that concept, the city of Chico adopted a TND code within their zoning code, with TND designations that range from less to most intense, consistent with the transect concept. And this is a floating zone, intended to be applied in various locations throughout the city as a framework that can be used to create new walkable complete neighborhoods. And the way the code works is that if the TND zone is applied to a specific property, it requires the preparation of a property-specific Regulating Plan and Circulation Plan. And that plan would need to identify allowed frontage types, building types consistent with the standards that are contained within the TND chapter zoning code.

So in Chico, the TND zone was applied to a property that is known as Marion Park. The project in the property is currently under development. And what you see on the screen is a diagram that’s illustrating the different parts and components of this development project.

[Note: The Chico TND zone as applied to Meriam Park is for an entirely new neighborhood. The development shown had been open land on the edge of the existing city.]

34:20

So here’s a model of the proposed development that’s currently under construction. This is showing an area with multi-family housing and open space. One of the requirements of the TND zoning district is that the regulating plan must include open space integrated into development. And there’s a standard that there must be one type of open space within a quarter mile of 90% of the dwelling units in the development. The code identifies the types of open space that are allowed within the TND designation. And it’s up to each individual regulating plan to come up with a configuration for the for the open space consistent with this requirement.

So here’s a model of the proposed development that’s currently under construction. This is showing an area with multi-family housing and open space. One of the requirements of the TND zoning district is that the regulating plan must include open space integrated into development. And there’s a standard that there must be one type of open space within a quarter mile of 90% of the dwelling units in the development. The code identifies the types of open space that are allowed within the TND designation. And it’s up to each individual regulating plan to come up with a configuration for the for the open space consistent with this requirement.

[Meriam Park is a 272-acre development constructed on previously open land by a single development company. They project 2,300 to 3,200 residences, with both single-family and multi-family units, and includes ~68 acres of total open space. Most buildings are 2-story, with some 3-story. Major plans were approved by the city in 2007, but development did not start until 2016 because of the recession. The website is https://www.meriampark.com/

From my perspective, Meriam Park is a perfect example of how a development can have lofty goals, can utilize Form-Based Code, can have a plan that uses all the right buzzword – and can still fail the community. It is promoted as being cycling- and pedestrian-friendly and of New Urbanist orientation, but, Reader: Look at these photos. Is this a neighborhood where you would want to walk?

There will be a separate article as a criticism of the Meriam Park development. It is promoted as New Urbanist — they even named a main building after Andrés Duany — but it has a bare few of the New Urbanist policies. It is an improvement over typical suburban sprawl, but not by much. ]

35:00

The TND zone also identifies allowed building types. Here is a rendering of one of the mixed-use buildings within the Merriam Park project. I think this probably is classified as a large mixed use-building within their system.

For this type of building, as with other building types, there are standards for building placement, minimum and maximum height, parking location, and frontage types. So the TND Zone allows for and calls for a range of housing types including row houses, or row homes. Standards attached to this building type include bill-to lines, minimum and maximum building height, ground floor elevation, parking placement.

[Note: Single-family homes have not been proposed in the Arcata Gateway plan, as it has been presented. Arcata’s need for housing units is cause for strong encouragement for multi-story buildings on a large scale.]

So here’s a photograph of housing that is constructed. The other images were graphics and renderings of planned development. This this is a courtyard apartment building that has been constructed. With this housing type, within the TND code, there are standards related to central cart courtyard dimensions and parking location.

I think one of the things that’s interesting about Miriam Park is that through using the TND code, and they’ve succeeded in introducing a broad range of housing types, not just multi-family apartments or single-family homes, but a real range of housing types that increased choice, and I think contribute to an interesting diverse urban environment.

[Reader, again: Look at the photos. Is this what you would call “succeeded in introducing a broad range of housing types” ?]

Form-Based Code Example: Grass Valley Development Code

[Here’s the original image from the Ben Noble presentation. The Form-Based Code calls for a building maximum height of 3 stories, or 45 feet. The image shows a 4-story or taller building. The text reads: “Buildings taller than three stories will be allowed only with approved use permit.” In other words, over 3 stories requires a review process, with public input and, likely, Planning Commission approval.]

36:43

So a couple more examples of Northern California Form-Based Codes. Here’s an example in Grass Valley in the hills of the Sierras. Their zoning code establishes traditional community development zones that apply to specific areas in the city. There’s a town core, a neighborhood center, and neighborhood general zones. And attached to these zones are proscriptive standards, such as a build-to line — whereas in the traditional zoning districts there’s a minimum setback. In the traditional community development zones, there’s a build-to line requirements as minimum building frontage requirements, standards for street-facing building entrances, and other similar proscriptive Form-Based standards.

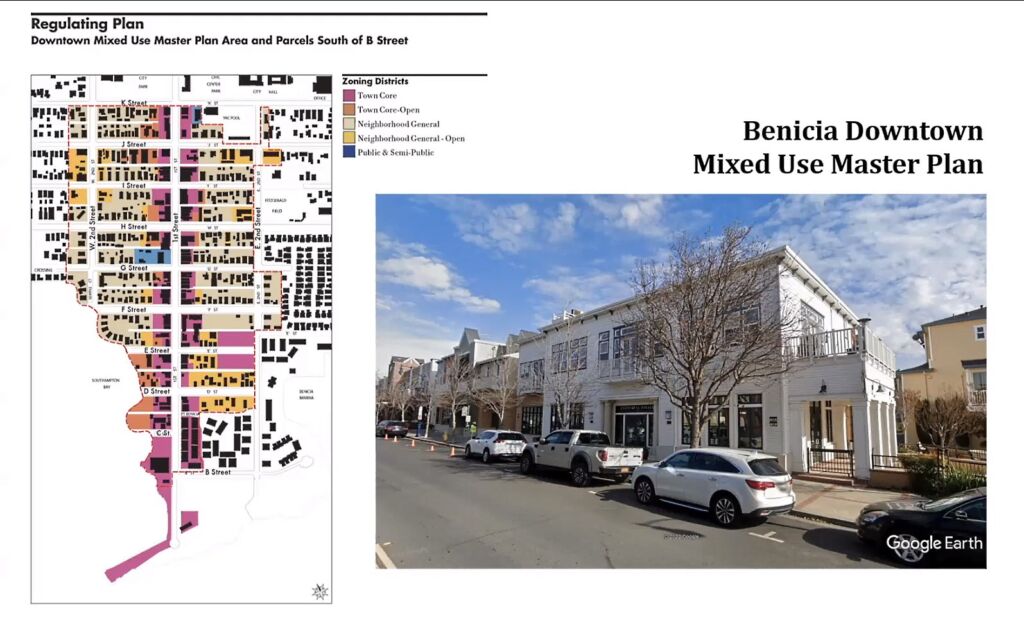

Form-Based Code Example: Benecia Downtown Mixed Use Master Plan

And my last example of a California Form-Based Code in a smaller community is in Benecia. This is a code I’m quite familiar with. I do a lot of work in Benicia. And they have a Form-Based Code that applies to their downtown Main Street and surrounding neighborhoods. And this is a historic district; Benecia’s a very historic city. Many of you probably know, it’s actually the location of the first capitol for the state of California before it was moved to Sacramento.

And my last example of a California Form-Based Code in a smaller community is in Benecia. This is a code I’m quite familiar with. I do a lot of work in Benicia. And they have a Form-Based Code that applies to their downtown Main Street and surrounding neighborhoods. And this is a historic district; Benecia’s a very historic city. Many of you probably know, it’s actually the location of the first capitol for the state of California before it was moved to Sacramento.

For the district that applies to their Main Street, 1st Street, there are standards for build-to lines, there’s a percentage of the building that must be built to the build-to line along the building, the primary street frontage. There’s minimum and maximum height standards, there’s a first-floor ceiling height. There’s parking location standards and allowed frontage types with standards. So the building that you’re seeing here has a frontage that opens out onto open space to the right – we can’t really see that there. And I think that’s incorporating what would be referred to as a Gallery frontage type, in keeping with the sort of historic character of development in downtown Benecia in the building typology.

Part 2: The Gateway Area Form-Based Code

39:06

39:06

Okay, so that is an overview of what a Form-Based Code is and examples of Form-Based Code from California. I hope that was informative and useful for you so that you’re coming out this sharing our perspective on what a Form-Based Code is and how it’s been used in other cities. I think that’s going to help us as we move forward and thinking about what the Form-Based Code for your area can and should be.

So in this part of the presentation, I’m going to move into why we’re preparing a Form-Based Code for the Gateway area and not more traditional zoning or some other approach. We’re going to lay out some guiding principles that are based on community feedback so far, and then we’re going to describe or I’m going to describe the anticipated contents of the Gateway Form-Based Code.

Here’s a summary of why we’re proceeding with the Form-Based Code for the Gateway area. And I think this reflects some of the things that I said previously when describing a Form-Based Code. We think that the Form-Based Code really is the best tool to implement the vision of the Gateway plan and to produce high quality housing that’s desired for the community. And we think it’s a better tool than a more traditional zoning regulations. And a Form-Based Code, we think, will be more usable, with graphics that are easy to understand to use. We think it will work well to help make a place in our placemaking efforts.

And because of Form-Based Code is proscriptive, saying what we want rather than what we don’t want, that helps to create a desired place, unlike more conventional zoning codes. There’s an emphasis on creating a quality public realm where private development is integrated with the public realm. It’s more predictable. Form-Based Code can deliver predictability for both the developer and for the community. This can save time and money for all involved in the development process and help attract investment into the communities. And then — land use flexibilities. We’re focused, we’re primarily interested in form, urban form and creating public spaces. And this creates flexibility so that the use of the building can adapt and evolve over time with changing conditions.

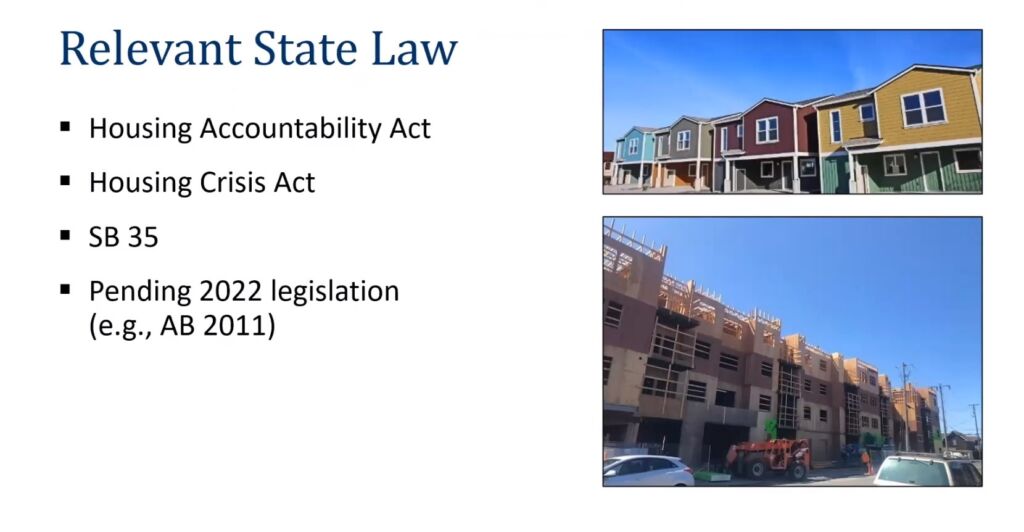

So another very important thing to think about in terms of why a Form-Based Code is State Housing Law and recent changes to State housing law. Recent legislation limits the city’s ability to deny multi-unit housing projects. Laws also require cities to rely on objective standards when approving or denying housing projects, and in some cases require by-right approvals for qualifying projects. So there’s the Housing Accountability Act. There’s the Housing Crisis Act as SB35, and then some pending legislation.

In terms of the Housing Accountability Act, this law has been around for a while, but it was recently updated and strengthened by the Legislature. And essentially what that says is that the city cannot deny a multi-unit housing project or reduced its density if the project is consistent with objective standards, unless the city finds that the project will result in a specific adverse public health and safety impact.

The Housing Crisis Act, amended the Housing Accountability Act, and among other things, prohibits cities from adopting new subjective requirements for housing projects. SB 35, many of you may be familiar with this. What that does is require cities to allow a streamline ministerial process for qualifying multi-family and mixed-use residential development that incorporates a certain percentage of affordable housing. In every year in the Legislature, we see new legislation that aims to streamline residential development and allow more developments by-right. And one of those that’s making its way through the legislature this year is AB 2011, which would require cities to allow by-right residential development in certain locations in districts that are zoned for commercial and industrial.

[Note: What Ben Noble is referring to as “Ministerial Review” is gone over later in this presentation; see the section starting at around 1 hour, 0 minutes. “Ministerial Review” can include public comment and Planning Commission approval.]

Housing production is an emphasis of the Gateway area plan. And I think a priority of the city as well to facilitate additional housing production, particularly an increased diversity of housing types of more affordable and attainable to all income levels.

[Yes: We must facilitate “an increased diversity of housing types of more affordable and attainable to all income levels.]

And we see the Form-Based Code as an appropriate vehicle to help achieve that objective. Part of the way that a Form-Based Code does that is increases certainty in terms of what is allowed and what is required and that in itself attracts investment. So if I’m a property owner, thinking about maybe developing my property with multi-family housing, if I have certainty about what is required of me and what is allowed, I’m much more likely to go down that path of developing that multi-family housing. Where if I lack it – if I don’t have that certainty — I may think about not moving forward. Another thing about Form-Based Codes is that they typically do not include density standards. So a density standard is often a number of dwelling units per acre. You might have [words?] a maximum of 30 dwelling units per acre, a Form-Based Code instead is concerned about the size of the building envelope.

And that building envelope can be divided into however many units an applicant, property owner or developer chooses. [In other words, the developer could choose to make 100 studio apartments of under 400 square feet… rather than a blend of studio, 1-bedroom, 2-bedroom, 3-bedroom apartments.]

So that incentivizes smaller units that are therefore more affordable. [But that may not be what is good for Arcata! We might need more 2-bedroom and 3-bedroom units.]

We also think that a Form-Based Code because of its emphasis on creating a quality public realm will help to create desirable neighborhoods that will attract investment and additional development. And then, lastly, the predictability of a Form-Based Code will help sustain community support to having a front-end and an agreement of what the important standards are for quality development to help sustain the plan in use.

46:43

46:43

Okay, so now some guiding principles. And this is based very much on things that we’ve heard through the public outreach up to this point, both for the Gateway area as well as other planning initiatives within the community. And we really want this code to support equitable and inclusive community. It’s imperative that code reflects Arcata’s unique visual character and allows for diversity and building forms and creativity in project design. The code must require development to support a pedestrian-friendly public realm, and to allow for a car-free lifestyle consistent with the city climate action goals. So as we proceed with work on the Gateway plan and the Form-Based Code, these principles will guide us as we move forward.

Anticipated Form-Based Code Contents

47:39

47:39

So now we’re going to move into the anticipated Form-Based Code contents. And this is our current plan and based on our thinking to date. We understand that some of this may change as we proceed with this work and obtain public input and continue to work on the documents. A lot of this content will be similar to examples that I provided previously in presentation. So we’re going to go through a few of these things.

The Form-Based Code will include a Regulating Plan. And in the Gateway plan, you may be familiar with a land-use designation map that identifies four districts: the Gateway Barrel, the Gateway Hub, the Gateway Corridor, and the Gateway Neighborhood. So we anticipate the Form-Based Code will, of course, have four main character districts that correspond with these land-use designations in a plan with development design standards that are unique and tailored to these districts.

The Form-Based Code will include a Regulating Plan. And in the Gateway plan, you may be familiar with a land-use designation map that identifies four districts: the Gateway Barrel, the Gateway Hub, the Gateway Corridor, and the Gateway Neighborhood. So we anticipate the Form-Based Code will, of course, have four main character districts that correspond with these land-use designations in a plan with development design standards that are unique and tailored to these districts.

[Note: There should be a separate district that corresponds with the Creamery District.]

49:15

Within those district standards, we will have forming character standards, addressing the important dimensions of urban design that I mentioned previously. And so part of that is going to be building places: Where on the lot do buildings need to be located. In higher intensity districts, we anticipate that buildings will be located closer to the front property line. In the lower intensity districts that are adjacent to existing single-family homes, we anticipate more of a setback with landscaping between the building and the street.

49:42

49:42

Building massing is going to be a critical part of the Form-Based Code for the Gateway area. We’re anticipating minimum and maximum building height standards, minimum and maximum building width standards. I think most importantly, standards to break up the massing of larger buildings in smaller volumes, standards that require variation of building heights, and standards that provide for sensitive transitions to adjacent lower intensity residential uses.

50:09

Exterior Design for this Form-Based Code I think will be important as well. Standards for windows and doors, building entrances, articulation, and forms. We’re going to be looking closely at existing development in Arcata, seeking public input on access to aspects of building design that are important to address in the Form-Base Code.

The Form-Based Code will address allowed land uses. But this is going to be a dramatic departure, we anticipate, from the land-use code that, as many of you know, includes an exhaustive detailed list of allowed uses and permits that are required for all of the different uses. That we want to move away from. We want to accommodate a wide range of residential, commercial, and employment uses in order in order to support a more fine-grain next. And we want to allow for the land-use next in the Gateway area to evolve over time and respond to changes.

The Form-Based Code will address allowed land uses. But this is going to be a dramatic departure, we anticipate, from the land-use code that, as many of you know, includes an exhaustive detailed list of allowed uses and permits that are required for all of the different uses. That we want to move away from. We want to accommodate a wide range of residential, commercial, and employment uses in order in order to support a more fine-grain next. And we want to allow for the land-use next in the Gateway area to evolve over time and respond to changes.

And we also anticipate that the Form-Based Code will include area-wide standards that are not necessarily district-specific. Some of the important issues within the Gateway area are historic resources and protecting historic resources, protecting environmental resources, promoting arts and entertainment, and adjusting mobility and parking in the Gateway area.

And we also anticipate that the Form-Based Code will include area-wide standards that are not necessarily district-specific. Some of the important issues within the Gateway area are historic resources and protecting historic resources, protecting environmental resources, promoting arts and entertainment, and adjusting mobility and parking in the Gateway area.

So we anticipate many of these standards for subjects such as these will be area-wide and not necessarily tailored to individual districts.

The code will also include streetscape standards. So within the plan, there are roadway design concepts. We anticipate translating these concepts into public improvement standards within the code that will be unique to street types, and may even be block-specific depending on the conditions.

The Gateway plan also includes an open space concept plan within the plan. We’ll translate that into public open space requirements, with standards for these open spaces that are established within the code.

52:40

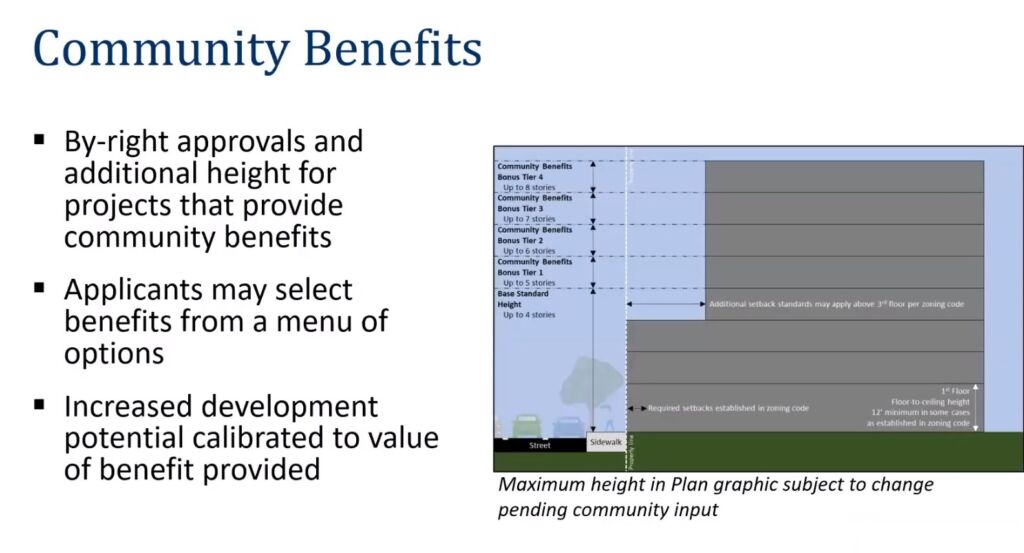

One thing in the Gateway Form-Based Code that’s maybe different from some of the other examples of Form-Based Codes is the importance of a concept sometimes referred to as Community Benefits. And the idea of Community Benefits is that a city establishes baseline standards for intensity. Let’s say if you’re regulating intensity by height, let’s say your baseline is three stories. An applicant can choose to provide define Community Amenities in exchange for increased allowed density. So, for example, if an applicant goes beyond minimum requirements, and provides some additional Community Benefits, the project can go to five stories or six stories depending on the nature of these benefits. [In the December 2021 draft plan, the Base Tier is shown as being 4 stories, with a project being able to go up to 8 stories depending on the amenities.]

One thing in the Gateway Form-Based Code that’s maybe different from some of the other examples of Form-Based Codes is the importance of a concept sometimes referred to as Community Benefits. And the idea of Community Benefits is that a city establishes baseline standards for intensity. Let’s say if you’re regulating intensity by height, let’s say your baseline is three stories. An applicant can choose to provide define Community Amenities in exchange for increased allowed density. So, for example, if an applicant goes beyond minimum requirements, and provides some additional Community Benefits, the project can go to five stories or six stories depending on the nature of these benefits. [In the December 2021 draft plan, the Base Tier is shown as being 4 stories, with a project being able to go up to 8 stories depending on the amenities.]

This concept is sometimes referred to as incentive zoning, is sometimes referred to as value capture as well. And it’s called value capture because what cities do is they say, “Okay, Applicant, you can build a more profitable project because of this additional intensity but we’re going to take some of that value and transform it into a public benefit.” It’s a common tool that many communities in California are incorporating, I’ve worked on a number of them. And one of the ways that we envision it working in the Gateway area is that for projects that provide Community Benefits, there would be by-right approvals and additional height in exchange for those benefits. An applicant may select from a menu of options to provide these benefits and that the increased development potential that would be provided as an incentive would be calibrated to the value of the benefit provided.

Part 3: Permit Requirements

54:50

54:50

So another part of the Form-Based Code would be permit requirements. And that takes us to the third and final part of this presentation. And it has its own part in this presentation because it’s particularly important. It’s a particularly important part of the code. And it’s also particularly important for our decision making on how to proceed with the code. So the permit requirements will influence the contents of the Form-Based Code, and our general approach that the code takes to regulating development in the Gateway. So we’re very interested in public thoughts on this subject. We’re also interested in obtaining Planning Commission and City Council thoughts on the subject when we reach that point. But we wanted to talk to you today a little bit about our thinking on this.

So I’m going to speak first about State law considerations and just describe our recommended Ministerial Process, and then go through a couple of different options for how this process could work.

So, as I mentioned previously, State law, the Housing Accountability Act, it’s been around for a while but it was recently strengthened. And for a long time cities in California were pretty much ignoring this law. Most people didn’t even know that it existed. Nobody was enforcing it. But as the housing situation in California got more problematic in terms of costs and affordability, the legislature strengthened the law and added new enforcement mechanisms.

So, as I mentioned previously, State law, the Housing Accountability Act, it’s been around for a while but it was recently strengthened. And for a long time cities in California were pretty much ignoring this law. Most people didn’t even know that it existed. Nobody was enforcing it. But as the housing situation in California got more problematic in terms of costs and affordability, the legislature strengthened the law and added new enforcement mechanisms.

56:16

So what the Housing Accountability Act does, as I mentioned previously, is that it says cities must approve multi-family and mixed-use residential projects that are consistent with objective standards, unless the project would have a specific adverse impact on the public health or safety. And cities may not deny a project or reduced the proposed density on the basis that the project conflicts with the subjective requirements.

So, essentially, if a project comes forward, and this project is consistent with all objective standards, whether the standards are within the Zoning Code or the General Plan or a Specific Plan, or design standards document — If the project is consistent, the city cannot deny it, cannot reduce the density unless it makes this finding a written finding based on the preponderance of evidence, which is a high bar to hurdle. And as I mentioned previously, the State agency Housing Community Development, as well as the State Attorney General’s Office, is actively enforcing on this law. And it’s really interesting to me to see how within just a couple of years, particularly in the Bay Area, there’s been such a focus and emphasis on what the HAA [Housing Accountability Act] requires, within the acknowledgement recognition that cities must comply. And it’s a law that is actively in force, not only by State agencies, but community organizations that are participating in the planning and entitlement process.

58:06

58:06

So given that is the framework that cities have to all have to operate in, in terms of State law, our recommendation is that the City only use objective standards to approve or deny a proposed multi-family or mixed-use residential project within the Gateway area. And when making this decision, the City would not consider project compliance with subjective requirements such as Design Review findings.

But the City can consider subjective requirements to make non-binding recommendations to an applicant. And this may seem radical, and this may seem extreme, but it’s actually more or less what State law is already requiring Arcata and other cities to do. So remember, HAA requires cities to approve a project if it’s consistent with objective standards unless this very difficult finding can be made. It does not allow the City to deny a project based on subjective requirements. So this Ministerial process, in many ways, is very consistent with what is already required by state law.

59:37

59:37

So with this Ministerial process there are a number of different options for how the process can occur. I’m going to describe three general approaches. The first being Over the Counter and the second being Zoning Administrator decision at a public meeting, and the third being Planning Commission decision at a public meeting.

[Note: In a small city like Arcata, it is typical that the position of Zoning Administrator is assigned to the Planning Department head, or, in our case, the Community Development Director, currently David Loya. It is also my understanding that the Zoning Administrator (or Community Development Director) can have another person as the Assignee, to take the place of the Zoning Administrator, either for a period of time, for a group of projects, or for a single project. That is, in our case, David Loya could assign a specific project to, say, Senior Planner Delo Freitas, and she would be the single person responsible for approving or denying the project.]

Approval Option 1: Over-the-Counter Process

1:00:05

With Option 1, you might think of this as an Over the Counter process. Planning staff would review the proposed project and would approve a zoning certificate for the project if it’s consistent with objective standards. There would be a public notice, but it would be a notice of Pending Decision so neighbors and the public could come to the Planning Department, look at the plans, and provide comments on the project. But there would be no public hearing. When staff makes the decision, either to approve the project because it’s consistent with standards or to deny it because it’s inconsistent, there would be the opportunity for an interested party to appeal to the Planning Commission, but the subject of that appeal would be limited to the determination of project conformance with objective standards.

[Note: In Arcata, the notice would go to neighbors within a radius of 300 feet – other means of notice are optional. How about having any Gateway area notice be posted on the City’s website, and sent to interested parties by e-mail… as being mandatory?]

1:01:38

1:01:38

Here’s a diagram that sort of summarizing what that process might look like. An applicant would submit the project; City staff would review the project for compliance with submittal requirements as well as objective standards; there would be a checklist of what the standards are, so that both the applicant, the City and the public know, in advance, what the project needs to comply with. There would be a public notice of a pending decision. And then the Zoning Administrator would make the decision, subject to appeal. Once the appeal period ends, the applicants could submit a building permit for the project.

So there are Form-Based Codes that incorporate a Ministerial Over the Counter approval.

And one of the best-known ones is the code for the Central Hercules plan, which has been around a while, that was one of the sort of early Form-Based Codes in California. With this plan for projects that are an allowed use and are consistent with standards the department staff would approve the application within 10 working days.

1:01:57

1:01:57

Another example of a Form-Based Code Over the Counter approval is in the city of Ventura. Ventura is a city that has enthusiastically embraced Form-Based Codes. They have Form-Based Codes for a lot of different areas in the city. And all of these codes include a provision where there are defined building types subject to specific standards, and if an applicant proposes a building type, consistent with those standards, it is exempt from what they call “planning permit” and could be approved by-right through a Ministerial, essentially Over the Counter.

Approval Option 2: Zoning Administrator Public Meeting

1:02:40

1:02:40

Okay, so the next option for how a Ministerial process can work, there could be more of a public process with the Zoning Administrator holding a meeting. So, again, the Zoning Administrator would focus his or her review on project conformance with the objective standards, but will make this determination at the noticed public meeting. At this meeting residents would have the opportunity to provide comment on the project. But action on the project would be limited to whether or not the project conforms to objective standards — that would be the sole basis to approve or deny the application. So this would need to be made very clear to the public that when acting on the product, the City can only consider a conformance to objective standards when making a decision on the project. And like with Option One, the Zoning Administrator decision could be appealed to the Planning Commission.

Approval Option 3: Planning Commission Public Meeting

The third option for the Ministerial process is similar to Option Two, but with the Planning Commission being the decision-maker on whether or not the project conforms to the objective standards. So like with Option Two, there’d be a notice public notice of a Planning Commission meeting and pending decision and residents would have the opportunity to provide comment at this meeting. But again, project conformance with objective standard would be the sole basis to approve or deny the application, with the Planning Commission decision being appealable to the City Council.

The third option for the Ministerial process is similar to Option Two, but with the Planning Commission being the decision-maker on whether or not the project conforms to the objective standards. So like with Option Two, there’d be a notice public notice of a Planning Commission meeting and pending decision and residents would have the opportunity to provide comment at this meeting. But again, project conformance with objective standard would be the sole basis to approve or deny the application, with the Planning Commission decision being appealable to the City Council.

There are cities who do something like Option Three that I’m aware of, in the context of SB 35 applications. As I mentioned previously, SB 35 is a State law where an applicant can request a streamlined Ministerial approval of the project if it incorporates affordability requirements, if it is consistent with all objective standards, it meets other eligibility requirements. And so what some cities do is that they provide for a public forum for the consideration of whether or not the SP 35 application is 1) an eligible project, and 2) is it consistent with all objective standards. And it allows for increased transparency, it allows for increased public awareness that that development is occurring, and allows for a public assessment of project conformance with an objective standards. I’m aware of one such process in Benicia, where I do a lot of work. And actually, tomorrow night, there is one such meeting of SB 35, the Oversight Committee for an SP 35 application. So this kind of process is something that you do see, but more within the context of SP 35 applications.

A couple of final thoughts on the advantages of a Ministerial process. I understand that there have been community questions about the Ministerial process, I think, reasonable concerns about the City losing the opportunity to evaluate, to exercise discretion on development projects on a case-by-case basis. Our assessment of this is that the Ministerial process is preferable because it reflects better what the City can and can’t do under the Housing Accountability Act. We’re concerned that continuing with the existing Design Review process for the Gateway area will generate frustration for neighbors who will be asking the City to exercise discretion that it actually does not have. And we think that it’s preferable to work with the public at the front end, to establish objective standards into approved project Ministerially upon finding that they conform to the standards.

A couple of final thoughts on the advantages of a Ministerial process. I understand that there have been community questions about the Ministerial process, I think, reasonable concerns about the City losing the opportunity to evaluate, to exercise discretion on development projects on a case-by-case basis. Our assessment of this is that the Ministerial process is preferable because it reflects better what the City can and can’t do under the Housing Accountability Act. We’re concerned that continuing with the existing Design Review process for the Gateway area will generate frustration for neighbors who will be asking the City to exercise discretion that it actually does not have. And we think that it’s preferable to work with the public at the front end, to establish objective standards into approved project Ministerially upon finding that they conform to the standards.

Opinion

[Note: “We’re concerned that continuing with the existing Design Review process for the Gateway area will generate frustration for neighbors who will be asking the City to exercise discretion that it actually does not have.”

First off, we are not intending on continuing with the current Design Review process. I propose that any notion you may have heard on that is false.

1: This is not necessarily a black-and-white situation. Within the objective standards of a Form-Based Code, there is room for interpretation. In an ideal FBC, two people looking at it would come to the same conclusion. But without seeing the code that is proposed, and without knowing how a FBC that we incorporate will be applied – and will evolve – into the future, we cannot now know how much interpretation will exist. Ideally, very little interpretation or discretionary review. In practice that may not be the case. We can understand what we have discretion over and what we do not. We’re concerned about public input in those areas where there is discretion – possibly because the FBC is not sufficiently clear or for whatever reasons, and with the impropriety of leaving that discretion in the hands of a single person.

2) “…will generate frustration for neighbors…” How about letting us figure out what is frustrating for us? With the appropriate clarity and awareness of the process, we as citizens can figure out what areas of choice are available to us and what areas are not. Yes, there may be some frustration among our citizens. And there will be other citizens here to explain to them how the objective standards do work and are applicable. Taking a choice away because it “will generate frustration” is not recognizing that we can have a wise and informed community here. If a developer presents a good project that meets objective standards and is of benefit to the community, it will be approved, I maintain.

3) “I understand that there have been community questions about the Ministerial process.” Well, to put it bluntly, we were presented with Option One – Zoning Administrator review with no public input and no Planning Commission review – as being what the “Ministerial Review” process is. We were not presented with Option Three, not one little bit.

In fact, what Ben Noble is calling “Ministerial Review, Option Three” was called here, over these past seven months, as Discretionary Review. We’ve been told that there would be no public input and that projects would not come before the Planning Commission. I brought up that, in the Redwood City Downtown Precise Plan, projects over a certain size come before the Planning Commission, and they call that Discretionary Review. Many jurisdictions call that Discretionary Review.

But as Ben Noble points out here, if the Form-Based Code contains appropriate objective standards then any well-made project will sail through any review process because it meets objective standards. And that is just what a Principal Planner at Redwood City told me: They have public comment and Planning Commission review on all medium and large projects, and either the project is quickly approved – because the developer has done the necessary homework, and understands the Code and what the city is looking for – or else it is quickly denied, and it’s back to the drawing board for the developer. Very simple.]

So we’re really interested in having the community conversation about the permitting process and the Ministerial option. And your input on that subject, as well as everything that I presented tonight, and the additional outreach work that we’ll be doing is needed, it’s necessary, and it’s appreciated. And there’s going to be a number of opportunities to participate, including an upcoming City Council / Planning Commission joint study session, and community workshops and a range of different online engagement opportunities to make it easier for everybody to participate in this process. So with that, I will end my presentation. I really look forward to hearing your questions. I will hand it back over to David.

So we’re really interested in having the community conversation about the permitting process and the Ministerial option. And your input on that subject, as well as everything that I presented tonight, and the additional outreach work that we’ll be doing is needed, it’s necessary, and it’s appreciated. And there’s going to be a number of opportunities to participate, including an upcoming City Council / Planning Commission joint study session, and community workshops and a range of different online engagement opportunities to make it easier for everybody to participate in this process. So with that, I will end my presentation. I really look forward to hearing your questions. I will hand it back over to David.

Questions from the Community

David Loya 1:09:12