Tumeric can contain lead

Tumeric can contain lead

Recent articles in The Economist alerted us to the presence of lead compounds in the spice tumeric. For these articles plus links to other articles, see here, below.

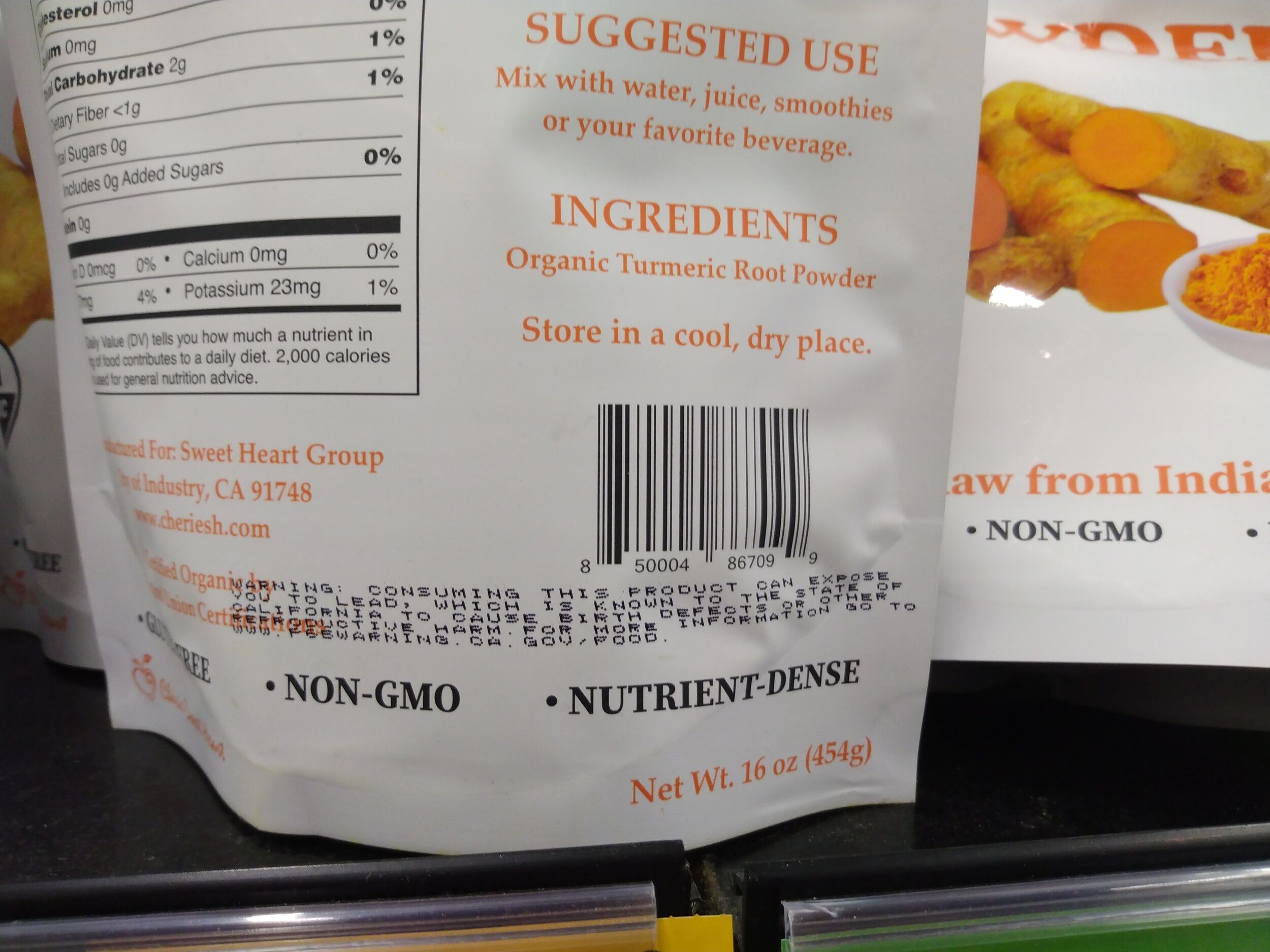

Shown here are some photos taken at a local market. We can note that the products are considered to be “organic” — and yet they may contain a toxic substance. Curiously, of all the packages of the “Certified Organic Tumeric Powder,” only one package had the warning. The warning appeared to have been printed separately from the printing of the package — on the other examples, the warning is a part of the original package design.

If you find other examples locally of tumeric with a warning label, please take photos and send them to me.

What is Tumeric ?

We are familiar with tumeric — the yellow spice that is used in curries. As a food additive, it is used to give warm color to mustards, butters, and cheeses. Since 2015, Kraft, the packaged food giant, has used tumeric, paprika, and annatto for coloring in its macaroni and cheese products, replacing formerly-used artificial colors.

As a health supplement, tumeric is beneficial for its anti-inflammatory and strong antioxidant properties, and is possibly helpful for hay fever, indigestion, osteoarthritis, gout, and more. The main bio-active ingredient in tumeric is curcumin. (For those of you interested in using tumeric for health reasons, you are likely aware that combining tumeric with black pepper will increase the absorption of curcumin. A substance in black pepper called piperine, when combined with curcumin, has been shown to increase bioavailability by 2000%.)

Lead Chromate is added to tumeric to brighten the color

The practice seems to have started after the Bangladeshi floods of 1988. The water damaged the crop and darkened the color of the tumeric roots. In order to stay competitive, the businesses that were grinding and processing the tumeric added lead chromate, locally known as “pueri,” to the powdered tumeric to enhance the color.

Lead chromate is a orange-yellow powder typically used in the paint industry, where it is called “chrome yellow.” Unlike other lead-based paint pigments, lead chromate is still widely used. Despite containing both lead and hexavalent chromium, lead chromate is not considered to be highly toxic because of its very low solubility. However the dust, when inhaled, is easily introduced into the bloodstream.

The practice of adding lead chromate spread, and soon much of the tumeric produced in the world contained lead chromate or lead oxide (“red lead”).

Nearly all of the world’s tumeric is grown and processed in India. About 80% of what is grown in India is also consumed in India. Other producers of tumeric include Bangladesh and Myanmar.

The FDA does not have guidelines for allowable amounts of lead in spices

The FDA’s allowable level of lead in candy is 0.1 ppm (parts per million). In Bangladesh, the allowable level of lead in tumeric is 2.5 ppm.

Most turmeric sold in the United States is imported from India and Bangladesh.

A 2014 study published by researchers at Harvard University reported lead concentrations of up to 483 ppm in turmeric samples collected from 18 households in rural Bangladesh.

A 2012 study of 32 samples of tumeric purchased in the Boston US area, showed a median level of concentration of lead of 0.11 ppm — about the level the FDA has for candy. However two of the samples had levels of 35 and 95 ppm — in other words, 350 times and 950 times the FDA allowable levels for candy. For more info on this study, see here.

Lead-Free Tumeric comes from Georgia, USA

There is a relatively small amount of tumeric grown in the Southern U.S., in particular by The American Turmeric Company in the very south of Georgia, just above Tallahassee, north of the Florida panhandle. They absolutely guarantee there is no lead in their products. For more info see their website and this article.

Recalls of tumeric in the US

Recalls of specific brands of tumeric occur in the US on a regular basis. In some cases, lead levels have been in the 30 to 50 ppm range. In 2016, 38,000 pounds of tumeric were recalled by a Florida wholesaler. Also in 2016, 337,000 pounds of curry were recalled. This was consumer-level packaged curry powder, recalled for lead contamination.

The following two articles are from The Economist in their November 2, 2023, issue. The two articles are similar, but contain different information. They’re short, so you can easily read both.

A team of researchers from Stanford University and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh recognized how the presence of lead in tumeric was a national health issue in Bangladesh. They were able to present their findings to top politicians in Bangladesh, including the now-four-time (since 2009) prime minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina. To her credit, it was Sheikh Hasina who supported the campaign to end the use of lead in tumeric processing. The articles suggest that the government of India could take similar action.

For a more in-depth article on tumeric production and the problems of lead poisoning, see The Vice of Spice: Confronting Lead-Tainted Turmeric in the on-line magazine “Undark.”

An article in the Stanford University News from 2019: Stanford researchers find lead in turmeric.

Stanford Medicine Magazine: The Spice Seller’s Secret: A hunt for the sources of lead poisoning in Bangladesh

From The Economist:

How to stop turmeric from killing people

Developing countries — especially India — should learn from Bangladesh

Tumeric, a flowering plant of the ginger family, has long been prized in Ayurvedic medicine for its anti-inflammatory properties and in Asian cuisines for its earthy flavour and vibrant hue. Haldi, the spice’s Hindi name, is derived from the Sanskrit for “golden coloured”. But for the millions of South Asians who habitually consume it, turmeric’s skin-staining yellowness can be deceptive and deadly.

To heighten their colour, the rhizomes from which the spice is extracted are routinely dusted with lead chromate, a neurotoxin.

The practice helps explain why South Asia has the highest rates of lead poisoning in the world. The heart and brain diseases it causes—to which children are especially susceptible—accounted for at least 1.4m deaths in the region in 2019. The economic cost is crippling; that year lead poisoning is estimated to have lowered South Asian productivity by the equivalent of 9% of Gross Domestic Product. Yet it turns out that with clever policies, enlightened leadership and astute messaging this blight can be greatly reduced. Bangladesh has shown how.

At the instigation of teams from Stanford University and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, a research institute, the country launched a nationwide campaign against turmeric adulteration in 2019. Rules against adulteration were enforced and well-publicized stings carried out against wholesalers who persisted in it. The prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, discussed the problem on television. Bangladeshi bazaars were plastered with warnings against it. Local media also publicized it.

According to newly published data, the country thereby reduced the prevalence of turmeric adulteration in its spice markets to zero in just two years. That slashed lead levels in the blood of Bangladeshi turmeric-mill workers by about a third. Nationwide, it probably saved thousands of lives. Early analysis suggests that each extra year of healthy life cost a mere $1 to preserve. Achieving the same benefit through cash transfers is estimated to cost over $800.

Other countries where lead poisoning is rife should follow Bangladesh. Recent estimates suggest a staggering 815 million children — one in three of the total number of children worldwide — have been poisoned by lead. According to the Centre for Global Development, a think-tank in Washington, this disaster explains a fifth of the learning gap between children in rich and poor countries.

The poisoning has many causes. Weak or absent regulators permit lead-infused cooking utensils, cosmetics and other products. Yet adulterated turmeric looks like a major culprit almost everywhere, chiefly owing to poor practice in India, which produces 75% of the spice. India was the source of much of the poisonous pigment found in Bangladesh and is estimated to have the highest incidence of lead poisoning of any country.

Bangladesh’s response to the problem, if properly understood, could work in many countries. Its key elements included an openness to foreign expertise; effective NGOs; a willingness by the government to work with them; and the formation of an even broader coalition, also including journalists and private firms, to maximize the effort. This low-cost, coordinated and relentless approach to problem-solving, familiar to admirers of Bangladesh, has underpinned its outstanding development success over the past two decades. And Sheikh Hasina deserves credit for it—even though her commitment to such enlightened policymaking appears to be flagging.

Leaders and lead poisoning

With an election approaching, the world’s longest-serving woman prime minister, Bangladesh’s ruler for two decades, is growing more authoritarian and irascible. The importance of the turmeric campaign should help persuade her to reverse course. As it shows, the Bangladeshi model rests on organising, collaboration and consensus, not political fiat, and there is much more than her legacy riding on it.

India, whose leader, Narendra Modi, is in the process of driving out foreign donors and dismantling any NGO he considers unfriendly to him, has much to learn from Bangladesh’s more open, pragmatic approach. The developing world has countless health and environmental problems that it might help solve. For these many reasons, it should be sustained and widely copied.

Bangladesh strikes a blow against lead poisoning

Are India’s rulers wise enough to take a lesson from their neighbor?

Tumeric is the key to a good curry — ask any South Asian. The spice supplies a distinctive flavor, aroma and bright yellow color. Many believe that consuming turmeric, or even bathing in it, also has multiple health benefits. But in much of South Asia, and perhaps far beyond, the spice also exacts a terrible cost.

That is because turmeric sold in these places is routinely adulterated with lead chromate in order to brighten its golden hue. And exposure to lead, a neurotoxin, increases the risk of heart and brain diseases.

Children are especially vulnerable, because lead poisoning stunts cognitive development. According to a study by the Centre for Global Development, a think-tank in Washington, lead poisoning among children in poor countries explains 20% of the learning gap between them and their peers in rich countries.

People in South Asia have the highest levels of lead in their blood, according to a new study published in the Lancet Planetary Health. Pinpointing the main cause had long seemed daunting, because lead is everywhere in the region. Traces of the metal can be found in cooking utensils, cosmetics and other everyday products. But in 2019 a team of researchers from Stanford University and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B), a health-research institute, began focusing on turmeric adulteration.

Working with the country’s food-safety authority, and politicians right up to Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh’s powerful prime minister, they then launched a nationwide campaign to root out the use of lead-chromate pigment in turmeric. It turns out to have been hugely successful, according to a new study published in the journal Environmental Research.

In less than two years, the share of turmeric samples in Bangladeshi markets that contained detectable lead fell from 47% to 0%. This elimination of lead adulteration had a near-immediate public-health impact. Among workers at turmeric mills, blood lead levels dropped by 30% on average. Across Bangladesh the reduction in lead exposure probably saved thousands of lives for little cost. A preliminary analysis by Pure Earth, a New York-based environmental NGO, suggests the programme delivered an additional year of healthy life for $1. (Generating the same effect through cash transfers is estimated to cost $836.)

In a region where rapid policy responses, let alone effective ones, are rare, Bangladesh’s success is all the more impressive. It was founded on recruiting support from policymakers by explaining the problem to them in a credible way, says Jenna Forsyth of Stanford University. Between 2014 and 2018, she and her colleagues collected data to demonstrate the link between turmeric consumption and high lead exposure levels among pregnant women in rural Bangladesh. Armed with these findings, the researchers were able to convince not just Bangladesh’s food-safety officials to take urgent action, but also the prime minister’s office.

The mass-media campaign that followed included graphic warnings about lead-tainted turmeric. Sheikh Hasina commented on the problem on national television. Around 50,000 public notices about it were plastered in markets and public areas. At a big turmeric processor, researchers tested workers’ blood samples to show how lead was poisoning those responsible for pulverising, colouring and packaging the tubers from which the spice is produced; then publicised the results.

Turmeric adulteration was declared a crime—and this change was also broadcast. A bust on a major turmeric producer was aired on tv. Two wholesalers were prosecuted in a mobile court for selling contaminated turmeric, a trial the media was again encouraged to cover. The wholesalers were convicted, fined and had much of their stock confiscated.

The Stanford team hopes to help launch similar campaigns in India and Pakistan, where they believe turmeric adulteration may be even more prevalent and deep-rooted. Much of the poisonous pigment used in Bangladesh was imported from India. The spice supply chain is also longer and more complicated in India than in Bangladesh, where a handful of wholesalers serve the entire turmeric market.

The broader lessons from Bangladesh are applicable to all sorts of policy problems, suggests Mahbubur Rahman of ICDDR, B. First, identify and cultivate the most influential champions for change, he says. The impetus they generate can then be sustained by launching broad-based coalitions. In Bangladesh this meant rallying researchers, government, media outlets and private firms to collaborate against poisonous spices. It was hardly a secret recipe for success; but, as when making curry, the challenge lay in putting the ingredients together judiciously.